You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

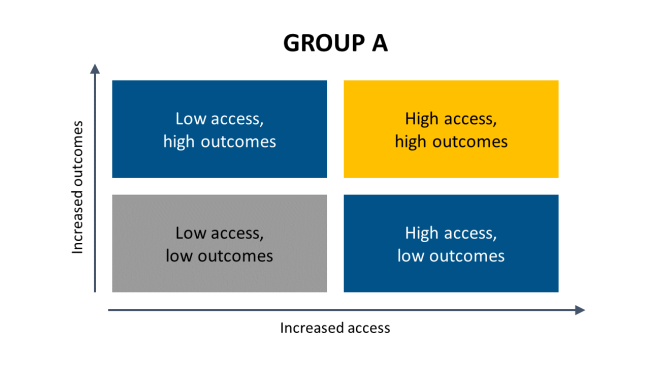

A proposed new classification would divide colleges into four categories based on access (enrollment of low-income and minoritized learners) and students’ economic outcomes.

American Council on Education

The American Council on Education (ACE) is proceeding with its plan to categorize colleges and universities based in part on how successfully they provide a “springboard to a better life” for their students.

The work is part of the higher education group’s multi-year overhaul of the Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education, a primary way that institutions, government agencies, ranking systems and others try to make sense of the thousands of American colleges and universities.

One of ACE’s primary goals upon taking stewardship of the Carnegie project two years ago was to inject into the classification system some measure of social and economic mobility, given the importance of that role in most colleges’ self-described missions and the growing public questioning about whether they are delivering on those missions.

This week, officials at the council offered the first look at how they hope to do that when the new classifications are released in early 2025: through a new “social and economic mobility” classification that would compare similar institutions on (a) access, or the socioeconomic and racial diversity of the students they enroll, and (b) the economic success of their learners after they leave, based on their earnings.

The access indicator is likely to focus on the proportion of students they enroll who are eligible to receive Pell Grants for needy students and who are nonwhite, compared to the socioeconomic and racial composition of the locations the students come from. The economic outcomes measure would focus on the earnings of students who receive federal financial aid, adjusted both for the geography of the job market the learners are working in and their race. (Details on this are below.)

“There’s no perfect way to measure social and economic mobility, but the Carnegie Social and Economic Mobility Classification aims to be a more intentional way of measuring how colleges and universities are delivering on their fundamental promise of being socioeconomic engines that empower students to reach their fullest potential,” Mushtaq Gunja and Sara Gast, who lead the Carnegie project for ACE, said in a blog post about the new system.

The Role of Economic Outcomes

ACE’s work to remake the Carnegie Classifications has been guided by the reality that the classifications, originally a way for researchers to make sense of a complex ecosystem, had morphed into part of the reward structure (along with college rankings) that often encouraged institutions to pursue research dollars and admissions selectivity over other goals.

As ACE’s president, Ted Mitchell, put it in an Inside Higher Ed podcast episode in 2022, “we want to create multiple lanes of institutional excellence that are aligned with their missions, rather than asking them to reshape their missions to align with the classifications.”

The first step in that process was last fall’s announcement that the new classifications would create more, smaller groupings of institutions that would make it easier for institutions to compare themselves to actual peers, and would clarify and simplify the research categories to expand the ways institutions can show they prioritize research.

But the creation of an entirely separate social and economic mobility classification may be an even bigger deal—and could be more contentious.

Dissent might arise less because the new categorization seeks to recognize the extent to which colleges and universities are providing access to low-income and minority learners, than because meaningful numbers of people within higher education still bristle at defining a college education by economic outcomes.

“How disappointing that ACE is now buying into the false measure of academic outcomes in salaries,” Patricia McGuire, president of Trinity Washington University, said. “Salaries are not outcomes of higher learning but products of the labor market. The improper use of salaries to rate, rank or otherwise classify institutions of higher education betrays our purpose in advancing learning and knowledge for social improvement.”

She added: “The salary factoid insults every person who chooses teaching, social work, counseling, fine arts, public advocacy, nonprofit service and other very important fields of human endeavor that do not pay at the level of lawyers or engineers but that are, arguably, far more important for our communities and society.”

In many ways, ACE’s desire to change the classifications to better recognize and reward institutions that contribute to social mobility would benefit a place like Trinity Washington, which under McGuire’s leadership has transformed from a struggling women's college into a minority-serving institution with mostly low-income learners.

And the early shaping of the social and economic mobility classification (which will be refined in response to feedback in the coming months) is designed to avoid some of the problems McGuire and other critics of economic mobility indicators tend to cite, such as racial bias in the job market, geographic differences in how much learners earn and the tendency of some fields to pay less than others.

Separating Access From Outcomes

In designing the new classification, which they did with help from a technical panel and a group of college and university leaders, Gunja and Gast said they believed it was important to differentiate between access and outcomes rather than “smushing them together” as many indicators of social mobility do, Gunja said.

The first indicator would look at whether institutions are “providing access to a student population that is representative of the locations they serve.”

This would be determined using data from the Education Department’s Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System on enrollment of Pell Grant–eligible students and those who are “non-white.” Gunja said ACE was leaning toward focusing on the latter, as opposed to looking only at underrepresented minority students, say, because currently there is no accurate way to disaggregate Asian-American students by those who come from disadvantaged backgrounds versus those who do not.

An institution’s enrollment data would be compared to U.S. Census data about the racial and socioeconomic makeup of the areas where its domestic students come from. That might be two or three nearby counties for a community college, or 20 to 25 states for a private college or flagship university with a national footprint.

An institution would be categorized as either “high” or “low” access, depending on how its proportion of low-income and minority students compares to the populations of the areas it serves. This approach would try to avoid questions such as “is a 30 percent Pell rate good or bad? Is 50 percent students of color good or bad?” Gunja said.

When it comes to outcomes, Gunja acknowledged the philosophical objection that McGuire raised about defining college outcomes by salary alone. He said it was important to be clear about what the classifications “are measuring and what they’re not. We’re not trying to assess the full value of a college degree. There are lots of other incredibly important reasons to go to college. We are not assessing those.”

The way that ACE and Carnegie are currently planning to gauge post-college earnings would be to focus on an institution’s students who receive federal financial aid, which is what the College Scorecard would track.

To mitigate one practical concern that critics cite about the limitations of earnings data—that colleges enrolling many students of color can be penalized because those learners “enter a racialized labor market and earn less”—ACE plans to compare the incomes of an institution’s learners to “the salaries that black and brown and white and Asian students make in the locations where those learners go to work,” Gunja said.

The other major objection—McGuire’s qualm that colleges would be penalized if their graduates go into fields such as teaching, social work, counseling and public advocacy—would be dealt with, in part, Gunja said, by the fact that colleges would be compared in the new basic classifications mostly to peers with similar mixes of programs of study.

“Engineering schools will be grouped together on one end and design schools on the other,” he said.

In addition, the data ACE is using shows that “it’s not really teachers that are dragging down the salaries of students,” Gunja said. While fields such as fine arts tend to pay less, “what really drags down salaries are a lack of good completion rates. If you’ve completed and you’ve got a job, even as social workers, you’re doing OK and not dragging the institution down.”

Potential Implications of the Mobility Data

The Carnegie Classifications are important mostly because of how they are used, like when governments or foundations use them to decide which institutions are eligible to receive grants, or college rankings groups use the categories to divide which institutions it ranks against one another.

Similarly, the significance of the revision of the classifications may depend on whether and how others embrace approaches like the social mobility categorization. Wide usage of these indicators, for instance, could result in more visibility for colleges that focus on access over selectivity and prioritize strong student outcomes over research, say.

On the question of adoption, Gunja said he is encouraged. “I’m pretty optimistic about the possibility for take-up here,” he said. “We’ve talked to funding agencies that are trying to diversify the pipeline of institutions they give money to, and they’re really interested in having information about social and economic mobility to help them.”

a818.jpg?itok=YusUVfky)