You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

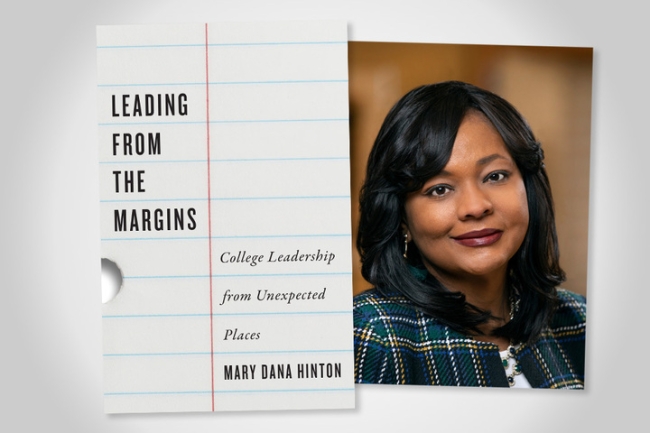

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | Hollins University

In her new book, Leading From the Margins: College Leadership From Unexpected Places (Johns Hopkins University Press), Hollins University president Mary Dana Hinton recounts with warmth and candor how her experience growing up far outside America’s traditional power centers gave her the strength and vision to develop her own inclusive, expansive style of leadership.

The child of a poor single mother in rural North Carolina, Hinton was marginalized by race, gender, socioeconomic status and geography. She credits her mother’s drive, courage and commitment to education with inspiring her to attend Williams College and ultimately pursue a Ph.D. and a career in higher education focused on promoting equity. Hinton served as president of the College of Saint Benedict in Minnesota from 2014 to 2020 and then became the 13th president of Hollins—a small women’s college in Virginia—in August 2020.

She discussed her new book with Inside Higher Ed via Zoom. Excerpts of the conversation follow, edited for length and clarity.

Q: What does it mean to lead from the margins?

A: To me, leading from the margins simply means that I get to embrace those characteristics that other people want to throw aside or say I should be ashamed of or that I have to “overcome”: my race, my economic background, my sex. So often, you’re told that you have to be a certain type of leader in order to be successful. And I believe that those of us in the margins bring unique and powerful strengths to leadership that are needed today, that uniquely equip us in this moment. And that it’s really important that others in the margin see themselves as leaders as well.

Q: How does one derive strength from being in the margins?

A: I think you have to set aside for a moment this notion that there’s only one way to lead. All too often leadership theories suggest there’s a certain way to be in the world in order to be viewed as a leader. And that way of being does not resonate with those of us who come from lower-income communities … Women are often excluded. People of color or other minoritized groups, we’re told you have to look and sound and act a certain way to be a leader, when, in fact, I believe that you garner unique strengths from each of those demographic characteristics that I named and that it’s important for the world to know that you can embrace who you authentically are and derive great leadership strengths there.

I want emerging leaders to know that their strength isn’t in how well they emulate someone else; their strength comes from their own story. I want to dismiss this notion that if you aren’t from the center, then somehow you aren’t a leader, or that you’re a leader despite being a Black woman. I’m the type of leader I am because I am a Black woman from a poor rural community—not despite that—and those characteristics actually give me strength in this role.

Q: One thing I found interesting is that you write about how the goal of leaders in the margins is not actually to get to the center, but rather to sort of pass through the center and maybe wind up in another part of the margin with different people.

A: You know, I wrestled with that a lot. And it was really freeing for me when I landed at the point. For a long time, I thought if I could just be like everyone else in the center, then I will have arrived as a leader. And I didn’t like this notion that for me to have “made it,” I had to become someone other than who I am. I realized over the course of my own evolution as a leader that my goal isn’t to be like people in the center; my goal is to go to the center, connect, have great relationships, encounter, embrace … but then to get to other people in the margins and encounter and embrace and uplift them as well.

Q: You’re describing a sort of versatility in the ability to navigate both spaces, the center and the margins. How hard is that for most people to achieve, and how receptive is the center to embracing people from the margins?

A: If you talk to many leaders who come from underrepresented groups, they would tell you that we’re often having to code-switch in various spaces. What I’m actually calling on folks to do, perhaps, is a little bit less of that. When you show up in the center, show up as who you are. When I’m in the center, I’m still a Black woman from rural North Carolina who grew up in impoverished circumstances—that’s who I am. I’m also calling for people in the center to welcome folks from the margins in as they are and to not decree, “You have to be a certain type of person to be in the center.” And to not suggest that somehow you’re not a leader if the center is not what you aspire to. I am asking those in the center who are willing to do the work to do the work. But I’m no longer judging my leadership or my ability based on how those in the center perceive me.

Q: It takes a lot of strength and confidence to develop that point of view. Where did yours come from?

A: I think it came from a few places. It came from my mother, who never had a birth certificate, so whose humanity was contested from the moment she was born, but who was so courageous and so strong and fought so hard for me to get an education. If my mom had the courage to go through all she did so that I could get an education, then I believe it’s my responsibility to be courageous for the next generation and make sure that other young people have the opportunity to get an education.

The second place is wanting to feel like I am enough as a human being. I think every human deserves to feel like they are enough. And that is not a message that very many young women are getting today: that you are enough, that you bring strength and courage into the conversation. So my desire to share that message that you are enough also drives a big part of this.

And the third piece is as we look to the future of higher education, as we look at the students we are so fortunate to serve—first generation, low income, students of color—they deserve to know and to be leaders. They deserve to see other leaders from the margins. A lot of my educational experience was mired in shame. And I don’t want that for the next generation.

Q: Most readers will likely be at least somewhat familiar with the challenges you describe connected to your identities as a woman and a person of color. But I think being from the rural South is not necessarily understood to be a marginalized identity. Can you talk about how that impacted you?

A: My identity really is a rural identity. I know what it’s like to live in such a community, particularly pre-internet. I grew up in the ’70s and ’80s, so you were very constrained by what you had around you. And we just didn’t have much. During that time, there was a lot of emphasis on supporting kids from urban environments and giving them opportunities; those opportunities didn’t make it to rural communities.

At the same time, there’s a richness to that rural experience, where you connect with others, where you hear the stories, where you understand what it’s like to be overlooked. And I think when I realized how overlooked I had been, in part because of being from a rural community, I wanted to shine a light on that and on the ways we stereotype or stigmatize. And I have to tell you, one of the remaining bastions of bias—one of many—is against people from the rural South. You are assumed to be less smart, not as savvy; you’re assumed to not be a leader. I often tell people that I worked so hard to get rid of my southern accent because it became abundantly clear to me when I went to college that people viewed me as less than because I was southern. And I was from the rural South; I wasn’t from a big southern city. There are layers of assumptions that people put on those of us from rural communities. And I continue to see that today.

Q: You write that the ability to connect with people is one of the most vital parts of your success as a leader. Do you think coming from the margins gives you a special knack for that?

A: I do. And I want to say, I don’t view life as a zero-sum game. So I’m really not trying to speak to the shortcomings or the strengths of people in the center. But for people in the margins, we do connect with one another. When you’ve been rejected, when the world tells you that you are lacking in who you are or your humanity is somehow less, I think you do look for other people to pull close. You try to have those conversations that say, “I see you, and I believe you. When you say you had this experience, I believe you, because I know what it’s like to be dismissed.” And I think one of the strengths in coming from the margins is a willingness and an ability to sit with other people to hear their stories, to affirm their humanity and to believe in who they are and in the potential they bring—not despite being from the margins, but because they’re from the margins.

Q: You also write about the importance of making yourself vulnerable as a leader. How does that fit in?

A: That’s probably the question I get asked the most about leadership: why would you make yourself vulnerable? Because when we envision a leader, we don’t envision someone who’s vulnerable; leaders are supposed to be strong and decisive and authoritative. But I believe that for me to be the leader I need to be of this community, I need to be willing to show people my heart. I need to talk about those things that make me want to dwell in the margins. Why am I proud of being from the rural South? Why am I proud to be a first-generation college student? I have to share those things. And some people will choose to reject you because you make yourself vulnerable. But those are not the people by whom I judge my success or my ability.

I think that notion of “leaders aren’t vulnerable” is really damaging. To me, vulnerability and courage are twins. You get your courage when you look at your own story and the stories of those around you and you decide, “I’ve got to make a difference.” But you can’t decide you’re going to make a difference without spending a lot of time thinking about your own vulnerabilities and journeying alongside others in their moments of vulnerability.

Q: It’s a little bit of “I’ll show you my humanity if you show me yours.”

A: One hundred percent. And I think one of the deep losses in society right now is we are either afraid to show one another our humanity, or we’re afraid to hold gently the humanity of another. That’s true whether you’re from the margins or the center. And until we get to a point where I can look at you and see your humanity first, I don’t know how we become a society committed to the common good. I guess you could boil the book down to that: I just want people to see the humanity of those of us who come from the margins and to see it as bringing its own unique strength.

Q: In the book, you write that the two critical strategies for leading from the margins are authenticity, which we’ve covered, and a sense of mission or vocation. Can you talk about how that impacts your approach to leadership?

A: This notion of mission and vocation—I hope it transcends college leadership. Everyone who aspires to lead should understand why they want to be a leader. If it’s about the trappings of the job, then it’s probably not the right job. Leadership is so hard today, it has to be something you do because you cannot imagine doing anything else. I lead a college today in this really challenging moment because I believe in an educated citizenry, I believe in democracy and, most of all, I believe in educational equity. That’s what gets me out of bed.

f917.jpg?itok=cjynvv9F)