You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

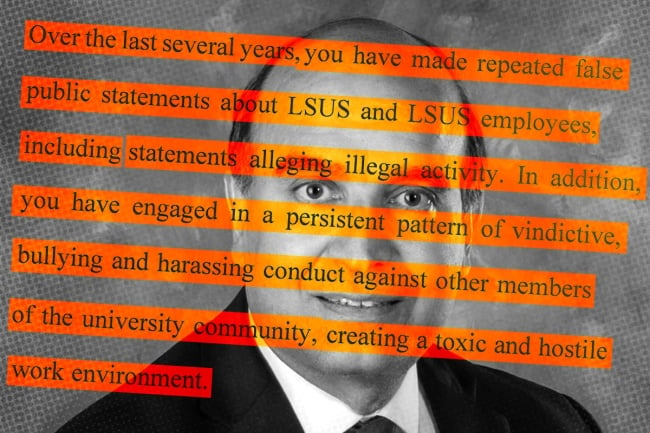

Louisiana State University at Shreveport is trying to fire Brian Salvatore, a tenured chemistry professor. It has accused him of, among other things, “creating a toxic and hostile work environment.”

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | Photo and document provided by Smith Law Firm

Louisiana State University at Shreveport is trying to fire a tenured professor. Brian Salvatore is defending himself by noting that all the allegations against him relate to speech he says is protected, including about local environmental hazards.

He’s received support from a state-level American Association of University Professors official, a retired Army lieutenant general who led a security review of the U.S. Capitol after the Jan. 6, 2021 breach, plus community members who appreciate his anti-pollution work.

Who isn’t speaking up for Salvatore, a chemistry professor? Numerous colleagues, including leaders of the Shreveport faculty and staff senates. In fact, they had reported him to human resources, LSU Shreveport chancellor Robert T. Smith wrote in a Nov. 8 letter. (Salvatore’s lawyer provided that letter, which the university declined to confirm or deny.)

Smith’s letter listed the university’s charges against Salvatore and told him he was being placed on leave and barred from campus, with his email access cut off. “Over the last several years, you have made repeated false public statements about LSUS and LSUS employees, including statements alleging illegal activity,” Smith wrote. “In addition, you have engaged in a persistent pattern of vindictive, bullying and harassing conduct against other members of the university community, creating a toxic and hostile work environment.”

A week before Smith’s letter, three liberal arts department chairs had written to him saying their faculty senators were considering resigning from that body due to an atmosphere that, as Smith put it, “has single-handedly been made toxic by Dr. Salvatore.”

“I did not bully, I did not disrupt, all I did was speak about repeated violations of state law and university policy,” Salvatore told Inside Higher Ed.

A faculty committee will now recommend to Smith whether to fire Salvatore, and Smith will make a recommendation to LSU president William F. Tate IV. Salvatore has accused his colleagues of incompetence, plagiarism and open meetings violations, allegations that variously came after another faculty committee didn’t award him a sabbatical and a faculty grievance panel didn’t support his grievance. “He deliberately—maliciously so—tried to besmirch me,” one of Salvatore’s fellow professors, Alex Mikaberidze, told Inside Higher Ed.

In spring of 2021, Mikaberidze, a history professor, said he chaired a committee handling a grievance Salvatore filed—Mikaberidze declined to discuss what the allegations were. In December 2022, after the grievance didn’t go Salvatore’s way, Salvatore contacted Oxford University Press editors to accuse Mikaberidze of plagiarism, Smith wrote in the university’s list of charges.

The publisher cleared Mikaberidze, wrote Smith, who added that it’s “quite apparent that Dr. Salvatore’s efforts were intended solely to tarnish the reputation of a prominent colleague, in apparent retaliation for Dr. Mikaberidze’s service on the grievance committee.”

In November 2022, LSU Shreveport’s Faculty Senate passed a resolution asking Salvatore to apologize to the sabbatical committee after he—according to the meeting minutes’ recounting of the Faculty Senate president’s remarks—called the sabbatical committee members incompetent and asked for their resignations. Salvatore alleged that the Faculty Senate meeting had violated open meetings laws, and he called the Senate’s executive committee “a little cabal,” the minutes say.

Some of the university’s charges are more strange. Smith wrote that Salvatore has continued to publicly accuse the former LSU Shreveport chancellor of making “sexual advances” toward Salvatore’s wife. Smith wrote that it was instead Salvatore’s wife, a fellow professor there, who displayed “inappropriate behavior” toward the former chancellor. In an affidavit rebutting the university’s charges, Salvatore said he believed the former chancellor “paid undue attention to my wife.”

Salvatore also accused university leaders of removing from his Apple iCloud account photos of a dead former employee. Salvatore, in his affidavit, wrote that he had taken photos of the body of a department chair that he and another colleague found dead of an apparent heart attack in the department chair’s home. The university police chief investigated and “found this allegation to be unsubstantiated,” Smith wrote.

Smith seemingly anticipated Salvatore’s free speech defenses. “These charges are not directed toward any exercise of free expression or academic freedom on the part of Dr. Salvatore,” Smith wrote in his Nov. 8 letter. “LSUS acknowledges that faculty, including Dr. Salvatore, have a First Amendment right to speak on matters of public concern. This right does not extend, however, to making defamatory or false statements that cause reputational or other harm.”

Smith even cited the AAUP's seminal 1940 Statement of Principles on Academic Freedom and Tenure against Salvatore, noting it says that faculty members, when speaking publicly, “should at all times be accurate, should exercise appropriate restraint [and] should show respect for the opinions of others.”

Salvatore’s lawyer, J. Arthur Smith III, told Inside Higher Ed that “the unique thing about the case is they’re proposing his termination on the basis of the content of his speech.” He said all 13 of the university’s charges concern speech, and LSU Shreveport’s administration is “doing some pretty fancy talking out of both sides of their mouths” about this fact. “It’s patently unlawful and unconstitutional in our view,” he said.

Kevin Cope, an LSU Baton Rouge English professor and treasurer of the AAUP Louisiana Conference, has been publicly defending Salvatore. “I believe that Brian is a very reliable person,” Cope said.

Cope said Shreveport and its LSU campus are conservative places, and “this is a person who’s been engaged in a lot of social causes that are not altogether popular in a conservative environment.” (Alongside Salvatore’s anti-pollution work, he also mounted a failed 2019 run as a Democrat for the Louisiana House of Representatives.)

As for the university’s long list of charges, Cope said “I think what the administration is attempting to do is throw all of this stuff together in a single basket to try to suggest a lifetime pattern of aggressive behavior and also to try to confuse the issue, to create the fog of war.”

Environmental Advocacy, or Creating a ‘Toxic Environment?’

About a decade ago, Salvatore began speaking out against plans to openly burn chemicals from Camp Minden, a Louisiana National Guard site near Shreveport that contained military explosives. The Louisiana Illuminator has reported that he continues to raise concerns about open burning at Clean Harbors—a site in Colfax, La., about 2 hours southeast of Shreveport, that disposes of Camp Minden’s outdated munitions.

Salvatore also wrote in his affidavit that, in December 2021, he spoke about the dangers of fracking for natural gas near Shreveport’s local water supply. His affidavit suggests that university administrators began retaliating against him for his environmental speech. “I firmly believe that my proposed termination is motivated as a response to the exercise of my rights under the First Amendment,” he wrote.

But, at a termination hearing earlier this month, university officials said the move to fire Salvatore isn’t about his environmental efforts or free speech, but his disrupting of shared governance, the Illuminator reported. They also said his allegations regarding the university using Clean Harbors were defamatory, that news outlet reported.

The university’s letter of charges against Salvatore includes a screenshot of an alleged March 2023 social media post, in which Salvatore posted photographs of what appear to be lesions, bruises or other marks on people’s bodies.

Salvatore allegedly wrote, alongside the photos, “look what (former) LSUS chancellor Larry Clark and his administration are doing to the people in Grant Parish by sending the university’s hazardous waste chemicals to be open burned and open detonated by Clean Harbors Colfax.”

But the university said none of its hazardous waste had been sent to that disposal location. The university didn’t provide Inside Higher Ed an interview. “Since this is a personnel matter, we are very limited in what details we can share publicly,” a university spokesperson said in an email.

The university’s letter listing the charges said Salvatore had received three formal reprimand letters, in 2020, 2021 and 2023. “When faculty speak or write as citizens, as in the case of your social media and other public observances, and when they make and sustain false allegations, the reputation of the university and the public’s confidence in it may suffer,” the letter said.

Multiple LSU Shreveport faculty members mentioned in either the documents in Salvatore’s case or Faculty Senate minutes didn’t respond to Inside Higher Ed’s requests for comment or referred Inside Higher Ed to the university spokesperson.

Among them was the Faculty Senate president, Cassie Williams. According to the university’s list of charges, Salvatore wrote that Williams “is violating both policy and law” and “jeopardizing her very prospects for tenure,” after which Williams complained to human resources. Salvatore wrote in his affidavit that he never threatened or bullied Williams.

Mikaberidze, the professor Salvatore accused of plagiarism, said he does “respect Dr. Salvatore as a scientist, I respect him for his activism and for environmental causes.” But as for being a “colleague” and a “professional on campus,” he said there are “a lot of problems there.”