You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

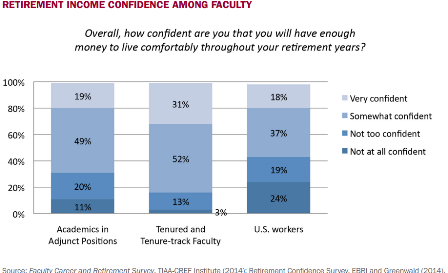

Just 19 percent of adjunct faculty members say they’re very confident they’ll have enough money for retirement, while another 49 percent say they’re somewhat confident at best. Nearly one-third of adjuncts (31 percent) say they’re not confident they’ll be financially able to retire at all.

Those are the findings of a new report from TIAA-CREF Institute, the research arm of TIAA-CREF, which is a major provider of financial services and retirement planning to colleges and universities.

The results -- based on a national survey of some 500 part-time and full-time, non-tenure-track faculty members -- are hardly surprising. That is, many adjuncts report that their relatively low pay makes it hard to make ends meet at the end of the month, let alone put money away for retirement. But the data nevertheless shed new light on a perhaps neglected subtopic of the national debate over adjunct working conditions. And while some advocates for adjuncts say that the reality for many is worse than what this study found, they hope TIAA-CREF’s attention will jump-start overdue conversations.

“A major portion of college education is being conducted by adjuncts, and we need to treat them properly,” said Mary Gray, a tenured professor of mathematics and statistics at American University who studies economic equity and education issues, after reviewing the report.

Adjuncts and Retirement

Some 82 percent of adjuncts said they’re saving for retirement, either through a plan at work or on their own, according to TIAA-CREF’s report. Some 74 percent of adjuncts in the sample have the option to contribute to a retirement savings plan at the college or university where they work. Some 60 percent of adjuncts with that option are exercising it, while more than half of those who don’t have retirement plans through their institutions wish they did. The report does not specify whether colleges with programs open to adjuncts match their contributions.

“The top reasons cited by academics in adjunct faculty positions for a lack of confidence in their retirement income prospects appear interrelated -- 28 percent do not feel that they are saving enough and 33 percent cite low earnings,” reads the report. About one-third of adjuncts also say they don’t have confidence that Social Security as they know it will exist when they intend to draw on it.

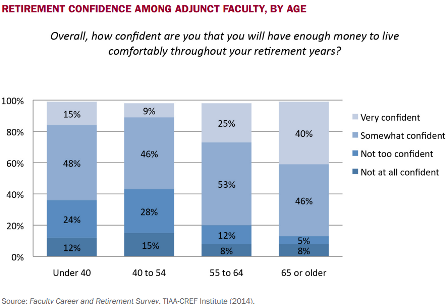

Some 15 percent of adjuncts under 40 say they’re very confident they’ll have money for retirement, compared to 40 percent of adjuncts 65 or older. About 48 percent of those under 40 say they’re somewhat confident, while 46 percent of those 65 and older say they are.

Adjuncts in the liberal arts tend to be less confident than their peers in the professional disciplines: 37 percent in the liberal arts are not confident, compared to 21 percent in the professional fields.

Debt likely also is impacting the ability of adjuncts -- especially younger ones -- to save for retirement. About half of adjuncts say debt is personally problematic, and 13 percent consider it a major problem.

Career Satisfaction

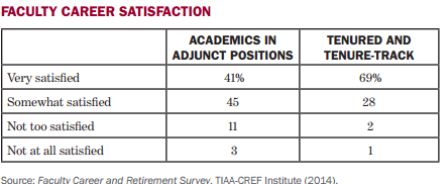

TIAA-CREF also asked adjuncts about career satisfaction, and compared their responses to similar questions posed to tenured and tenure-track faculty members (who were also included in the survey but are the primary subjects of a separate report released earlier this month). The results suggest that adjuncts enjoy the nature of and want more academic work, but feel they’re underpaid. They also parallel the findings of a 2010 study of adjuncts from the Coalition on the Academic Workforce.

“The top reasons adjunct faculty give for not being ‘very satisfied’ with their careers are level of pay (cited by 25 percent), not having a full-time positions (23 percent), not having a tenure-track position (22 percent) and lack of job security (14 percent),” TIAA-CREF notes. So “it appears that the lack of a tenure-track position is not the issue so much as the lack of full-time employment for a number of academics in full-time positions.”

Comparatively, level of pay and poor work-life balance are the top reasons tenure-track faculty members are not very satisfied with their academic careers.

In terms of institutional support, adjuncts reported being most satisfied with teaching supports: 56 percent were “very satisfied,” for example. Satisfaction is lowest regarding institutional support for research, with 27 percent not satisfied (although 34 percent were still very satisfied). The study notes that while 99 percent of respondents reported having teaching duties, 31 percent say research is part of their job. TIAA-CREF assumes this more of a “self-requirement” that might assist in securing a tenure-track position or promotion.

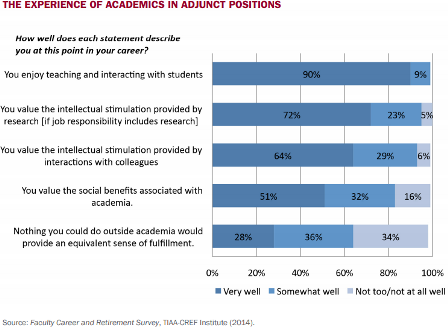

Adjuncts most value students, with 90 percent saying they enjoy teaching and interacting with them. Nearly 30 percent of adjuncts feel strongly that nothing they could do outside academe would provide an equivalent sense of fulfillment -- although about one-third of adjuncts say they could find another similarly fulfilling job outside of higher education.

Unsurprisingly, adjuncts with the lowest household incomes were more likely to report career dissatisfaction. There’s no statistically significant difference in satisfaction between adjuncts teaching at private and public institutions. Community college adjuncts are slightly more likely than their peers elsewhere to cite low pay as the primary cause of their dissatisfaction.

TIAA-CREF’s sample does not include what it calls “professors of the practice,” or those who have primary work outside the academy. It’s also weighted by age according to the larger 2010 study of adjunct faculty by the Coalition on the Academic Workforce. It should be noted that that report, which did include professors of the practice, found a much lower rate of availability for institution-based retirement plans for adjuncts: 41 percent.

More than 60 percent of the adjuncts surveyed by phone for TIAA-CREF by an independent firm were under age 55, and nearly 30 percent were under 40. Women made up 52 percent of the sample.

Some 79 percent of respondents were employed at one institution; 17 percent were employed at two. Four percent were employed at three or more institutions. Just about two-thirds (67 percent) of respondents worked at public institutions. They were roughly split between doctoral-, master’s-, baccalaureate-, and community-level colleges and universities. Some 65 percent of respondents worked in the liberal arts, 32 percent worked in professional fields and 2 percent worked in other fields.

One-quarter of respondents said their 2013 income was $50,000 or less. Some 30 percent of adjuncts said their income was $100,000 or more, which TIAA-CREF says indicates a partner or other family member earning a relatively high income.

Age seemed to affect adjuncts’ perspectives, with older adjuncts more likely to be satisfied with their work experience. Some 52 percent of those 55 to 64 and 64 percent of those 65 or older said they were very satisfied with their careers. But just 35 percent of those under 40 and 29 percent of those 40 to 54 were very satisfied. The oldest adjuncts in the survey were the least likely to say they desired a full-time or tenure-track position.

Paul Yakoboski, a senior economist at TIAA-CREF Institute and author of the report, said the organization wanted to look at how adjuncts, not just tenure-line faculty, thought about retirement. While there wasn’t anything particularly shocking about the data, he said, comparing tenure-line and adjunct faculty attitudes about retirement and career satisfaction proved interesting. While there’s a big overall satisfaction gap between the two groups, he said, they have similar views on more focused questions.

Yakoboski said he didn’t notice any major push among institutions to include adjunct faculty members in their retirement plans, but he also said adjuncts might not know about the various options that are already available to them.

Important Conversations

Adrianna Kezar, a professor of higher education and director of the Delphi Project on the Changing Faculty and Student Success at the University of Southern California, has previously consulted TIAA-CREF on adjunct faculty issues. While the scenario presented in their findings might be “bleaker” for many adjuncts, she said, TIAA-CREF’s focus will bring more attention to adjunct retirement concerns -- a good thing.

“I know of no institutions that think of the long-term financial future of adjuncts,” she said. “So I am really glad TIAA-CREF has started this conversation.”

Gray, the statistician at American, was more critical, saying TIAA-CREF’s methodology left much to be desired, including a larger sample size and more clarity about adjunct response rates and how contact lists were generated (TIAA-CREF says they were “representative” of the adjunct population, and not exclusive to those working at TIAA-CREF member institutions). But she credited the report with fueling discussion and with noting the differences between tenure-line and adjunct faculty in retirement attitudes.

Gray said part-time workers at public institutions in some states get shut out of Social Security, and that lawmakers should work to close gaps that keep adjuncts from benefiting from this kind of “security blanket” in the absence of meaningful retirement benefits.

And Social Security doesn’t necessarily help adjuncts much, even in states where part-time faculty members can draw on it, said Keith Hoeller, a longtime adjunct professor of philosophy at Green River Community College in Washington and author of Equality for Contingent Faculty: Overcoming the Two-Tier System.

“Social Security benefits are calculated based on earnings in your top 35 years,” Hoeller said via email, so if “you have some years when you have not worked or earned very much, as is often the case with graduate students, your benefits will be lower.” Additionally, he said, “years in which you earn little will also mean lower benefits. Since adjuncts are often impoverished, they tend to take benefits earlier, which means they collect less money overall from Social Security. Few adjuncts can wait to retire until they are 70, when their benefit amount will be highest.”

Pensions, too, are based on how much one earns, Hoeller said. And some adjuncts may not qualify for pensions, especially if they are considered independent contractors. Moreover, he said, adjuncts in states such as Washington have traditionally had high eligibility thresholds for pensions, meaning that adjuncts in some case would have had to take on course loads larger than what was typically allowed by the college to qualify.

Unions have had some success in this area. The 2010 academic workforce report found that unionized adjuncts were more likely to have access to health and retirement benefits (60 percent of unionized adjuncts said they had access to retirement benefits from their employer versus 28 percent of nonunionized adjuncts). Lesley University adjuncts affiliated with Service Employees International Union recently won enhanced benefits in their contract, including access to a retirement plan with a university contribution, for example, according to SEIU.

Still, Michelle Healy, an organizing director with SEIU, said that contract negotiations at the many campuses that have seen successful adjunct union drives in recent months are focused first and foremost on raising adjunct pay.

“This is the more glaring problem,” she said. “Adjunct faculty are being paid a rate that we routinely hear is near poverty level,” making it hard for many to “fathom” putting any money away for retirement.

Anne Wiegard, a board member for the New Faculty Majority, a national adjunct faculty association, said more retirement benefits are nevertheless an important part of the reform agenda.

“People should be talking about retirement benefits for adjunct faculty that are equitable in relation to benefits provided to full-time faculty,” she said via email. “This principle of equity is really part of the urgent, larger conversation about contingent workers in the U.S.: retail and restaurant workers, domestic workers, etc., people whose work is essential for the economy but whose contributions are undervalued or even invisible.”