You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | Kent Nishimura/Getty Images

As campus protests raged across the country and pro-Palestinian demonstrators were increasingly cast as antisemites, Khaled Beydoun feared the characterization was a disservice not only to Muslim students but also to their Jewish peers.

As an associate professor of law at Arizona State University and a scholar of the First Amendment, religion and national security, Beydoun was frustrated by what he saw as discussions of antisemitism overshadowing clear demonstrations of Islamophobia. He also disagreed with how the two prejudices were pitted against each other.

“To understand Islamophobia and the way it developed in the United States, you have to understand how antisemitism developed,” he said. “Once you see these two forms of bigotry as essentially arising from the same rotten core, you’re able to demystify the idea that they’re oriented against one another.”

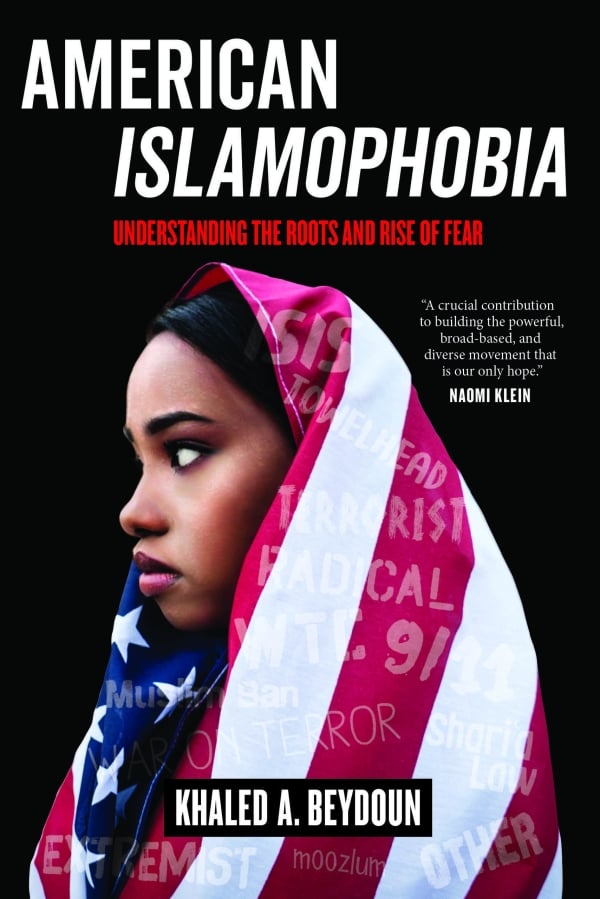

University of California Press

Beydoun, a Muslim himself, has used his 2019 book—American Islamophobia: Understanding the Roots and Rise of Fear,—and his academic and social media work since, to chart the historic roots and legal implications of Islamophobia in the U.S.

Inside Higher Ed spoke with Beydoun about his view on campus protests, and how he links them to widespread discrimination against Muslims that was inflamed after the terrorist attacks of 9/11. The conversation, edited for length and clarity, follows.

(Inside Higher Ed also conducted a Q&A on antisemitism with Benjamin Ginsberg on May 16.)

Q: For context, what do you think are the key events that have led us to where we are today?

A: I’ll be totally candid with you. Part of the reason I don’t like doing these interviews is because there are no succinct, cogent responses to a question of that kind. [Khaled had previously expressed hesitation about coming on the record after his quotes from past interviews had been taken out of context.] But I’ll try to answer as best I can.

First of all, Islamophobia is not directly tethered to what’s happening in Gaza right now. There’s some really interesting, concerning connections, but it’s not all direct. As far as how we got here, it’s as a consequence of the war on terror. Arab and Muslim identity has essentially been caricatured along with terrorist identities.

If individuals who are of Arab and Muslim identity are engaged in activity that is protected by the Constitution, like the freedom of assembly, speech, or to engage in unarmed dissent, they aren’t perceived, in the American imagination, as bona fide citizens who have legal and equitable access to those civil liberties. It’s not the starting point, but a critical extension point is the post-9/11 moment.

Q: What are your perceptions of recent pro-Palestinian protests and pro-Israeli counterprotests? And how do you think they’re related to the line between First Amendment rights and hate speech?

A: What I see on mainstream American media (or Western media for purposes of brevity) are these really unfair and strident characterizations of anything pro-Palestinian as violent. But that isn’t surprising because it conforms with the analysis that I just gave you. It’s also true for Black protesters. It’s less so the actual speech that is coming out of the mouths of the protesters, and more so the phenotype that raises this indictment of violence.

I’m not trying to construct a binary. There’s been some violence on both sides. But when there’s been extreme and egregious violence on the pro-Israeli side, it’s seldom covered, if not, entirely, not covered by media at the same rate. And when it is, you don’t have that characterization of violence.

Q: Is there credibility to the characterization of pro-Palestinian protesters as antisemitic? And where is the line between anti-Zionism and antisemitism?

A: I’ve researched Islamophobia and its history and lineage here in the United States. As a consequence, I also had to do that with the history of antisemitism. So for me this question has been extremely frustrating. Because if you know anything about antisemitism and the way it's developed in this country, the first thing you realize when examining Islamophobia is there are so many parallels. The roots of both, in many respects, are one in the same. So for me, the fact that people have these two things pitted against one another, is intellectually dishonest and the furthest thing from the truth.

The second thing is, it’s a very dangerous conflation to synonymize antisemitism with political Zionism. It’s entirely inimical to the First Amendment and free speech. Are you going to basically censor any individual’s ability to legitimately critique the State of Israel? It shrouds a nation state with the cloak that it’s religiously above that kind of criticism. We don’t do that with the Vatican.

To be frank, it does a real disservice to the legitimate forms of antisemitism that are proliferating across the country. There’s a wonderful quote: “If you diminish somebody else’s suffering, you also delegitimize your own suffering.”

Q: The House recently passed the Antisemitism Awareness Act< which aims to codify a definition of antisemitism into federal law. How would you define antisemitism and Islamophobia? And who should get to define them?

A: I don’t know who’s gonna be tasked with defining it, but the individuals who shouldn’t be defining it are politicians, who are not trained academics and have a clear-cut ideological bias. They’re the last people I want to define what antisemitism or Islamophobia means.

My definition of Islamophobia is basically religious animus that is advanced by societal and government actors. If I were to offer a definition on antisemitism, I would offer a sort of analogous definition. Both are disconnected entirely from being able to critique an individual, an entity, or a state.

I don’t think it’s Islamophobic when somebody comes out and says, “Hey, the Saudi regime is engaging in persecution.” Is it Islamophobic when you critique a government for doing horrible things? No, it’s a legitimate critique. Is it antisemitic when you critique the State of Israel for doing horrible things? No.

Q: Is it possible to protest peacefully and call out the humanitarian crisis in Gaza without being antisemitic?

A: Of course you can. Now, the reality is theoretically you can, but there’s always going to be an idiot in the crowd. Sometimes, there’s a deviant actor who says something that is insensitive and bigoted. Now, does that lone voice—whether it’s an Islamophobe or an antisemite—entirely undermine the entire protest as being bigoted? I would say no. Now if it’s coming from leadership, perhaps.

It’s also important to note that a lot of the most prominent voices on the pro-Palestinian side have been Jewish organizations.

Q: Are college campuses becoming more identity polarized generally?

A: Yeah, 100%. I think that’s also an outgrowth of a number of things. I think social media reifies and entrenches identity polarization because people are only following individuals who generally confirm what they already think. As a consequence of that groupthink, people become far more, not only narrowly ideological, but strident in their positions. When they finally face off with people in real time, during tense moments like this, it can definitely create really violent circumstances.

Also, a side point is the decline of traditional journalism. People are not consuming information as much from reputable outlets. They’re consuming it from podcasts. So instead of it being CNBC or CNN, now it’s a Joe Rogan, or a Ben Shapiro or a Candace Owens.

Q: What do you think about politicians’ role in this? Is legislation guarding against antisemitism being passed for politicians’ own gain? Or do they care about the protection of Jewish students as much as they say they do?

A: I don’t wanna make a sweeping assessment. But a lot of it, obviously, is political. A lot of it is driven by various lobbying organizations, driven by power, driven by the salience and importance of the State of Israel to the United States. Some politicians definitely care and should care. But that’s, in some respects, eclipsed by the political imperative to really serve the State of Israel.

Q: Have politicians taken similar measures to protect against Islamophobia?

A: No, not nearly as much. That’s really the most disenchanting strand out of all of this. We’ve seen—not only now, but ever since I can remember—considerable Islamophobia on campuses across the United States. Politicians, with rare exception, have not made this a primary focus or objective—largely because of the war on terror. It legitimizes this kind of bigotry.

Q: How can administrators and student affairs officials respond in a way that protects Jewish and Muslim students and free speech rights all at the same time?

A: I don’t envy their role. It’s a tough job that many university administrators have, especially on some of these campuses where things have become very violent. But look, UCLA’s president did a horrible job. As soon as you invite police on campus, that’s going to incite violence.

I think the baseline I would start with is that students have the right to engage in assembly and speech, and for it to be monitored by the university in a way that is stripped of racial and religious bias. And this is true for both sides. I would never want to police individuals who are aligned with the fate of Israel. There should be no content-based speech regulation, unless it’s advocating on behalf of genocide or advocating on behalf of bigotry. But you’ve got to start off with the baseline to allow students expression, and not bring in external police, because that’s when things tend to go downhill.

.jpg?itok=cjynvv9F)