You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Tuition discounting at private nonprofit colleges reached new heights this academic year, according to an annual survey.

AndreyPopov/Getty Images

Average tuition discount rates among private, nonprofit colleges continued to climb in the 2020-21 academic year as many institutions worked to retain and attract students during the pandemic, a new study from the National Association of College and University Business Officers found.

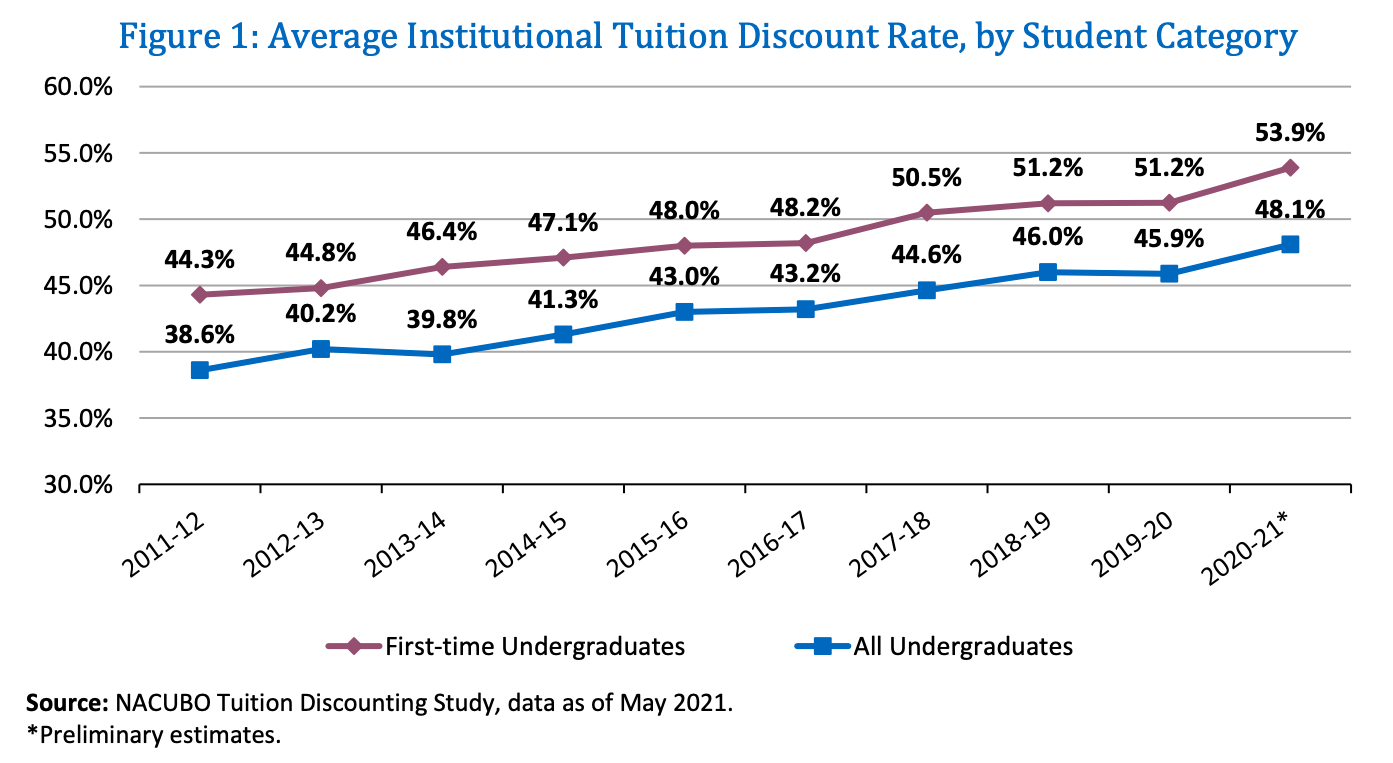

The average discount rate for first-time undergraduates reached 53.9 percent -- an all-time high -- during the 2020-21 academic year, according to NACUBO’s preliminary estimates released Wednesday. In other words, for every $100 in tuition colleges appear to charge on paper, they do not collect $53.90 from first-time undergraduate students.

Last year, the average discount rate held steady from the year prior at 51.2 percent, falling just short of predictions. The new study revised initial estimates that had shown the discount rate last year was tracking incrementally higher than the year before.

For all undergraduates, the average tuition discount rate in 2020-21 ticked up to 48.1 percent, a 2.2-percentage-point increase from the year prior, according to the study. During the 2019-20 academic year, the average discount rate for all undergraduates fell slightly from the year before, from 46 percent to 45.9 percent.

This year, NACUBO’s annual tuition discounting study is based on survey responses from business officers at 361 nonprofit colleges and universities across the country. The study defines the tuition discount rate for first-time undergraduates as the total institutional grant aid awarded to first-time, full-time undergraduates as a percentage of the gross tuition revenue an institution would collect if all students paid the sticker price. The formula for all undergraduates is similar.

The study focuses on institutionally funded scholarships, fellowships and other grants awarded to first-time, full-time students. It does not include grants from private organizations, governmental entities and organizations that require institutional matching funds where the outside organization develops the award criteria.

The study focuses on institutionally funded scholarships, fellowships and other grants awarded to first-time, full-time students. It does not include grants from private organizations, governmental entities and organizations that require institutional matching funds where the outside organization develops the award criteria.

Rising tuition discount rates can depress net tuition revenue per student if a college does not raise its sticker price in lockstep or line up other sources of funding to pay for financial aid grants. Colleges use targeted tuition discounting to entice more students or certain students to enroll, which can have the effect of raising overall net revenue -- making tuition discounting a closely watched, complex element of admissions and budgeting strategy.

For at least a decade, the average tuition discount rate for first-time, full-time undergraduates has increased slowly, rising 6.9 percentage points between 2011-12 and 2019-20. The pandemic exacerbated this well-established trend, said Ken Redd, senior director of research and policy analysis at NACUBO. And it did so when institutions are already expecting competition for students to increase.

“At some point, the pandemic effects will subside,” Redd said. “But the longer, much more troubling aspect is the demographic changes. With fewer traditional-age students leaving high schools and going on to college, it’s going to make the competition for new students become that much more fierce.”

Declining enrollment and rising competition for students will likely continue to push discount rates upward. Colleges likely won’t scale back their tuition discounting after the pandemic, Redd said.

“They may stay somewhat stable, or they may go up even faster, given those other factors besides the health effects of the pandemic,” he said.

Private colleges often advertise high sticker prices compared to public institutions. To enroll students who are unable or unwilling to pay those high prices, colleges employ tuition discounting strategies that subsidize a fraction of the sticker price through financial aid grants. As the competition for students gets more intense, private colleges will be pushed to increase their tuition discount rates in order to enroll the same number of students, Redd said.

Private colleges also use tuition discounting to jockey for better ratings in college ranking systems like those from U.S. News & World Report, Redd said.

Baccalaureate institutions on average use higher discount rates than master's, doctoral and special focus institutions, according to the study. During the 2020-21 academic year, the average tuition discount rate for first-time undergraduates at baccalaureate institutions rose 3.1 percentage points to 58.4 percent. Master's-granting institutions on average reported a 55.3 percent discount rate for first-time undergraduates, and doctoral institutions reported 50.2 percent. Special focus institutions have the lowest average discount rate of 38.5 percent.

During the 2020-21 academic year, nearly 90 percent of first-time students and 83 percent of all undergraduate students received some financial aid. Most students who received financial aid grants this academic year were awarded larger grants than in previous years, the study showed.

The vast majority -- 71.7 percent -- of institutional aid is funded through undedicated sources, which could include forgone tuition dollars, unbudgeted general funds or unplanned contributions, the study said. Just over 11 percent of undergraduate institutional aid is funded by endowment earnings, while 11.6 percent comes from institutional reserves and 5.5 percent comes from gifts and fundraising activities.

“Tuition discounting strategies come at a heavy cost for many colleges and universities, especially those that forgo a significant amount of tuition revenue to expand educational affordability for students and/or to meet enrollment goals,” the study said.

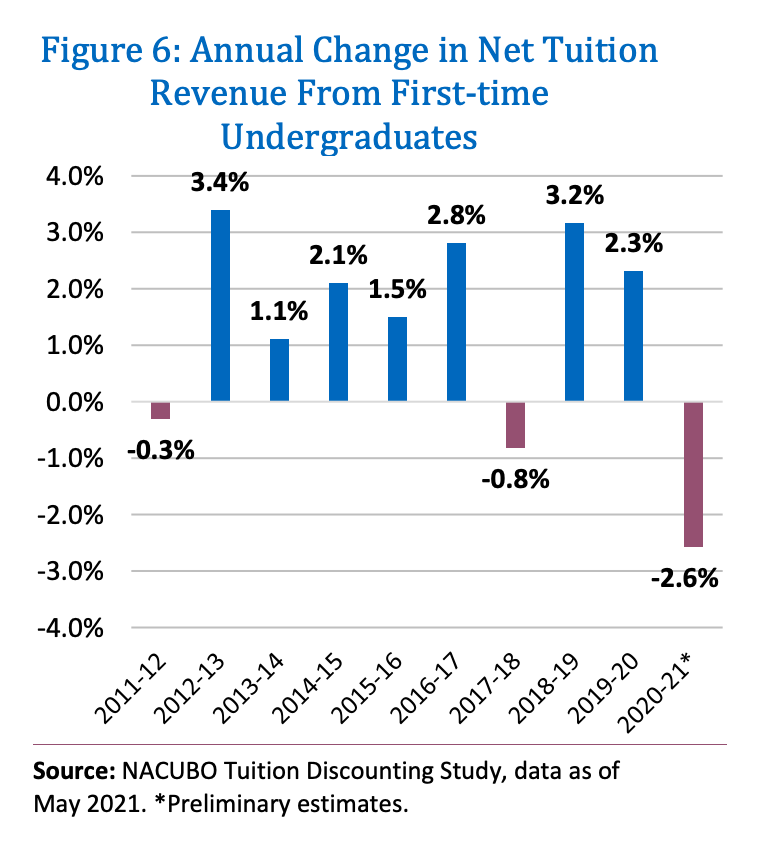

Annual changes in net tuition revenue have been volatile over the past several years, according to the study. During the 2020-21 academic year, average net tuition revenue for first-time students declined by 2.6 percent -- the largest drop in the last decade. Last academic year, average net tuition revenue increased by 2.3 percent.

This year, NACUBO asked college and university business officers about the potential long-term effects of the COVID-19 pandemic at their institutions. Eight in 10 business officers said that they’re anticipating significant changes in net tuition revenue and undergraduate student enrollment. More than three-quarters of respondents said they expect significant changes to room and board and other revenue, international student enrollment, and graduate and professional student enrollment.

Only 15 percent of business officers said they did not anticipate significant changes as a result of the pandemic.

Only 15 percent of business officers said they did not anticipate significant changes as a result of the pandemic.

Changes to learning modalities over the past academic year also caused changes to tuition and fee revenue for private colleges. More than 70 percent of business officers said their institutions charged a separate price for in-person learning and hybrid or online learning. About 14 percent said they did not charge separate prices but offered a discount for online or hybrid learning. Another 3 percent did not charge separate prices or offer a discount for online or hybrid learning, and 2 percent did not alter their tuition and fees at all.

Redd expects that online and hybrid learning will stick around, and so will separate pricing models.

“As more students come back to campus, I think you're going to see more of those students, even when they're on campus, want to take classes from a distance,” Redd said. “Whether that is hybrid or completely online or something in between, I think the days of the primary education of students being in traditional classrooms may have come to an end.”