You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

College presidents overwhelmingly remain white and male, the latest ACE presidents’ study shows.

Meet the new boss, same as the old boss.

When Pete Townshend of The Who penned those lyrics more than half a century ago, he almost certainly wasn’t thinking about the state of the college presidency. But those words aptly summarize the results of the latest American College President Study from the American Council on Education, released today, which finds that despite some diversity gains, college presidents continue to be mostly older, white and male.

Though racial and gender diversity has increased since the last study, conducted in 2016 and released in 2017, that progress is moving at a walk rather than a sprint. It is also failing to keep pace with the changing demographics of college students.

Now in its ninth iteration, the ACE College President Study, first produced in 1986, offers various insights into those who occupy executive offices at institutions of higher education. Data for the survey were collected in 2022, meaning the results here reflect answers from the last year. The survey—which was completed by more than 1,000 respondents last year—tracks race, gender, age and numerous other data points that offer a glimpse into the makeup of today’s college and university presidents.

Diversity Gains

So who are they? According to the ACE survey results, their average age is 60, 67 percent are male and 72 percent identified as white. That means 33 percent of presidents surveyed are female, and 28 percent identified as nonwhite.

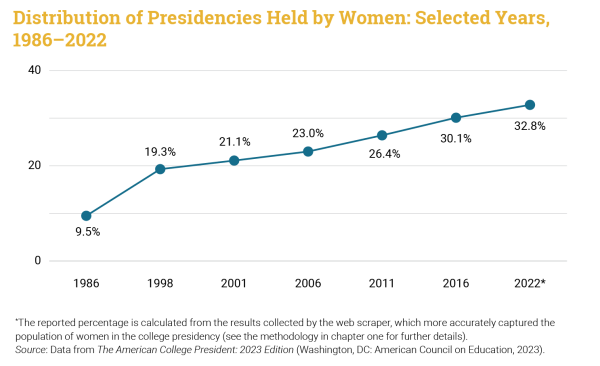

Female presidents have risen sharply since ACE first collected that data in 1986.

ACE American College President Study

Those numbers mark a shift from the survey released in 2017, which found that the average college president was 61.7 years old and 83 percent identified as white. While the executive office has diversified racially, the number of female presidents has increased only slightly. But that group was more diverse racially than their male counterparts; 69 percent identified as white, 14 percent as Black or African American, and 8 percent as Hispanic or Latina. No other group made up a significant percentage.

Among all nonwhite presidents, 13.2 percent identified as Black or African American; 5.7 percent as Hispanic or Latino; 2.8 percent as Asian or Asian American; and 2.8 percent as multiracial. No other race or ethnicity was reported at more than 1.5 percent.

Comparatively, the number of Black or African American presidents has nearly doubled since the 2017 release, which found they held 7.9 percent of such jobs among respondents. Likewise, Hispanic or Latino presidents have jumped from 3.9 percent to 5.7 percent in the most recent survey. No other group experienced a gain of more than two percentage points between the 2017 and 2022 reports.

“At a time when the sector is simultaneously managing complex issues such as ongoing fallout from COVID-19, troubling demographic trends, and declining public trust in higher education, diverse leadership is essential to addressing the challenges and opportunities ahead,” ACE President Ted Mitchell said in a news release. “As we continue to support the presidents who are thriving in these roles we must also work to inspire a new generation of leaders who are ready to take on these challenges and move higher education into a more dynamic and efficient future.”

However, some scholars suggest that finding a new generation of diverse leaders may prove challenging given that the pipeline to the presidency, typically through academe, lacks diversity.

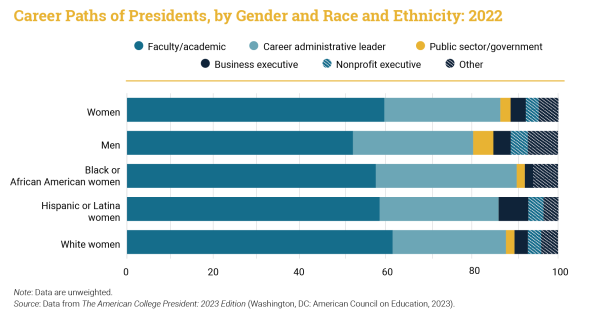

“The typical path to a university presidency is professor, department chair, dean, associate dean, then on to provost, associate provost or vice president, and then the presidency. So you have to look back at the professoriate,” said James Finkelstein, a professor emeritus at George Mason University who studies college presidencies. “If the professoriate is not dramatically increasing in diversity, you’re not going to have access to a larger pool of diverse candidates.”

According to the survey respondents, 53.8 percent rose through the faculty and academic ranks to reach the presidency while another 27.9 percent were administrative leaders in student affairs, auxiliary services, finance and other areas. The remaining 18.3 percent came from a mix of public sector/government, nonprofit, and business jobs, though 6.3 percent did not indicate their pathway.

Most presidents rose to their position through careers in academia.

ACE American College President Study

Shaun Harper, a professor of education and business at the University of Southern California, questioned the role that implicit bias plays among trustees tasked with hiring a new president to lead their college.

“Implicit bias is largely about implicit associations. If we keep seeing mostly older white men in the presidency, governing boards and search committee members will continue to unconsciously associate presidential leadership with this one archetype,” Harper said. Ultimately, he added, “this must change if the demographics [of presidents] are ever going to change.”

The boards that hire presidents also tend to lack diversity, noted Eddie R. Cole, associate professor of higher education and history at the University of California, Los Angeles.

“The demographics are not surprising. The college presidency is a powerful and influential position, and people in positions to hire presidents—board members, search firm executives—also tend to be white and seek people who fit the traditional model of ‘leader,’” Cole wrote in an email to Inside Higher Ed. “This explains why, despite rapidly changing demographics among students on many campuses, the college presidency remains majority white.”

Harper also raised the question of how colleges support presidents of color.

“These findings reflect current demographics, but what about racially and ethnically diverse presidents who were pushed out of their executive leadership roles?” Harper said. “It has been painful to watch so many extraordinarily talented, accomplished and promising people of color accept presidencies at institutions that were unprepared and unwilling to give them the chances they deserved. Recruiting more presidents of color is one thing—supporting, respecting and retaining them are also essential to increasing and sustaining diversity in these positions.”

Heading for the Exits?

On average, respondents said they’ve been in their jobs for 5.9 years. That number has fallen steadily according to each of the last three surveys, down from 6.5 years in 2016, seven years in 2011 and 8.5 years in 2006.

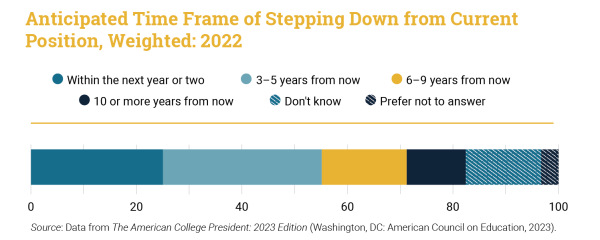

And more than half of presidents surveyed indicated they plan to depart their role within five years.

The survey found that 25 percent intend to step down “within the next year or two,” while 30.1 percent plan to leave within three to five years. Thirty-nine percent of presidents eyeing the exits are considering retiring and not taking another position, 27 percent are thinking about taking on a consulting role outside of a higher education search firm (while 16 percent said they would work at such a firm), and 23 percent are weighing moving to another presidency. Other considerations include the nonprofit or philanthropic world (16 percent) or joining the faculty ranks (12 percent).

More than half of college presidents plan to step down within the first five years.

ACE American College President Study

Those looking to leave within the next five years tend to skew older, at an average age of 67.7. And those planning to step down in the next year or two had an average age of 68.8.

The survey found that COVID-19 had little effect on planned transitions, with only 9 percent answering they were leaving earlier because of the pandemic; another 9 percent indicated that they intended to stay on longer because of the coronavirus.

Most presidents—59 percent—are not preparing for a successor. Of those who are, 81 percent indicated that their planned successor was already working at their current institution.

If half of college presidents leave in five years, that will open doors for more diversity, said Hironao Okahana, ACE assistant vice president and executive director of Education Futures Lab.

“Such an anticipated change in leadership, particularly among already underrepresented groups, will not only affect the diversity of the presidency, it will also impact several hundred institutions and the many students, faculty and staff who attend and work at them. However, these future vacancies also present an opportunity for more women and people of color to ascend to the college presidency,” Okahana said in a news release accompanying the survey results.

While the face of the college presidency has been slow to change over all, it has done so at some particularly influential institutions. Six of the eight Ivy League institutions will be led by women following formal transitions this summer. And Harvard University hired the first Black president in its history in December, announcing that Claudine Gay would move from her role as dean to president this summer.

Hiring Gay could—or perhaps should—have ripple effects, some scholars suggest, setting an example for other universities as she takes over one of the nation’s most visible institutions.

“Harvard hired an irrefutably qualified Black woman to serve as its next president,” Harper said. “For better or worse, many higher education institutions have historically followed Harvard’s lead. They should do so again by searching for and hiring irrefutably qualified presidents of color.”

.jpg?itok=cjynvv9F)