You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

International student enrollment grew across academic levels and fields of study in 2022–23, with especially strong growth in graduate enrollment.

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | Getty Images

International student enrollment skyrocketed in the 2022–23 academic year, surpassing pre-pandemic levels and landing at over one million students, according to the new “Open Doors” report from the Institute of International Education.

American institutions hosted 1,057,188 international students last year, a 12 percent increase over 2021–22 and the fastest rate of growth in 40 years. International students represented 5.6 percent of the total higher education student population.

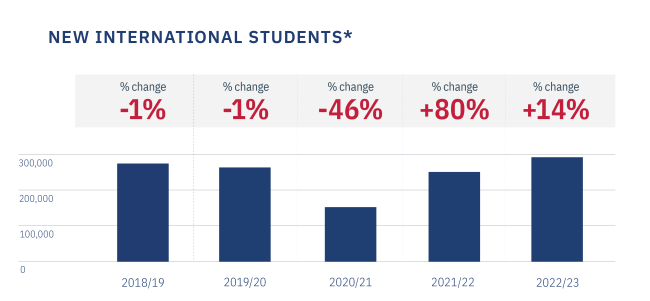

First-time international enrollments were particularly robust. The number of new international students grew by 14 percent in 2022–23, “soaring beyond pre-pandemic levels” and building on the 80 percent partial pandemic rebound of 2021–22 to reach a “near all-time high,” according to the report. It’s a welcome recovery for the international student market, which was predictably pummeled by the pandemic.

“We were very happy to see this rebound, and especially happy that it happened so quickly, just three years after the pandemic,” said Mirka Martel, IIE’s head of research, evaluation and learning.

Courtesy of the Institute of International Education

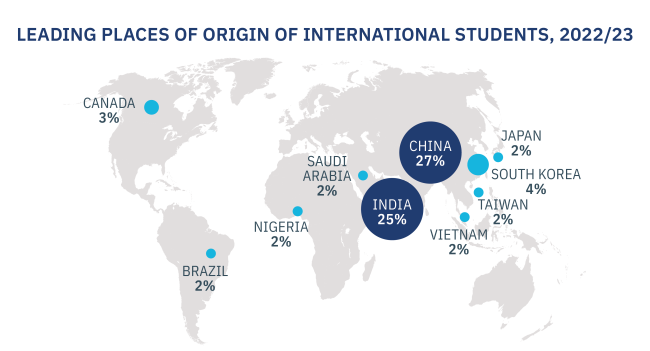

Despite a small decrease of about 0.2 percent, China remained the top country of origin for international students, with 289,526 studying in the U.S. But India, which has long been second to China, saw enormous growth: 35 percent year over year, reaching an all-time high of 268,923 students in the U.S. and inching closer to taking the top spot. Countries in sub-Saharan Africa also saw significant growth, sending 18 percent more students to U.S. colleges than in 2021–22.

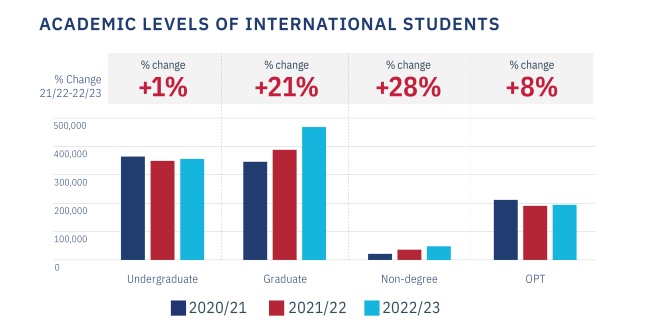

International student enrollment rose across all degree levels and fields of study for the first time since the 2014–15 academic year. But that growth was concentrated most heavily in graduate programs, which saw a 21 percent increase—the largest in the report’s history, according to Martel. Undergraduate enrollment, by contrast, rose by a little less than 1 percent.

Courtesy of the Institute of International Education

The report also noted the number of U.S. students studying abroad, though those data are a year behind international enrollment statistics. In 2021–22, U.S. study abroad numbers rebounded to about half their pre-pandemic level, which the report’s authors called a “critical turning point.” Nearly half of those who studied abroad did so during the summer, and the top destinations remained the same as in recent years: Italy, the U.K., Spain and France.

A New Juggernaut

The surge in interest from India and sub-Saharan Africa portends a changing post-pandemic international student landscape, especially as applications from East Asia are on a slow but steady decline.

Rajika Bhandari, principal of Rajika Bhandari Advisors and co-founder of the South Asia International Education Network, attributes the shift to a number of related factors, chief among them diverging demographic trends. While China’s traditional college-age population is stagnating, India’s is growing at a rapid rate, as is its ascendant middle class.

Courtesy of the Institute of International Education

She added that the boom in Indian international students could explain the disparate growth rates between the graduate and undergraduate levels.

“Most students coming from India are at the graduate level. This has always been the case and likely will be for the foreseeable future,” she said. “Therefore, just from a recruitment and revenue perspective, they are never going to have the same impact on an institution’s bottom line as the Chinese undergraduate students.”

Indian students also tend to be “far more price conscious,” Bhandari said, making the common destinations for Chinese international students—selective private institutions with high tuition, such as New York, Northeastern and Columbia Universities—less likely for the growing Indian international student pool.

“We need to be careful that we don’t think of India as the new China,” Bhandari said. “It is not.”

Still, the Open Doors 2023 fall snapshot suggests students from China may begin returning in larger numbers now that Beijing has lifted the travel restrictions put in place as part of its zero-COVID policy. Thirty-six percent of U.S. institutions surveyed reported an increase in Chinese international students this fall, up from 29 percent in 2022.

Bhandari believes the increase in students from countries like Ghana and Bangladesh is a positive sign of a more diverse, and thus sustainable, international market moving forward.

“In the past, U.S. institutions have tended to put all the eggs in one basket, whether it was Brazilian students or Saudi students coming, then the Chinese undergraduates,” she said. “I think there have been some real lessons learned about the need to diversify their efforts to recruit a broad range of international students.”

‘Dark Clouds’ and Silver Linings

William Brustein, professor emeritus of history at West Virginia University who served as the university’s vice president for global strategies and international affairs until 2020, said the pivot from China to countries like India, and subsequent lower undergraduate enrollment growth, could be an issue for institutions hoping to return to the revenue-boosting international enrollment market of the mid-2000s.

“China was a godsend for international higher education. You had a booming middle class that put a premium on education and would spend their last penny to pay that full fare,” he said. “God, we were reaping the benefits … I don’t see China bouncing back, and I don’t see what it brought being replaced.”

Without those monetary returns, Brustein fears U.S. institutions will be reluctant to commit the resources needed to sustain international enrollment growth.

“If the revenue is not flowing into these universities, they will continue to cut back on their investment in international offices that oversee recruitment,” he said. “And if you’re not investing in those offices, then you’re basically not going to see a significant change.”

Brustein sees some silver linings—namely Vietnam and Nigeria, both of which have the same burgeoning middle classes and cultural emphases on education that fueled the China boom. Both countries also saw some of the highest growth in 2022–23: a 5 percent increase from Vietnam and 22 percent from Nigeria.

But enrollment from those countries is not growing fast enough to make up for the tapering of Chinese students. That factor, coupled with the proliferation of less expensive but good-quality universities in countries closer to them, like Singapore and Japan, dampens Brustein’s hopes.

“We can benefit from building those pipelines [from Vietnam and Nigeria]. But we’re going to have to be smart about it and find ways to reduce the cost and offer more hybrid options,” he said. “That to me is one bright star … but it won’t reverse the overall decline.”

The Open Doors report heralds a positive future outlook: preliminary data for 2023 show an 8 percent increase in international student enrollment across higher ed institutions, with undergraduate enrollment rising to 2 percent—which Martel said she expects to continue as the pandemic recedes further into the past.

“Undergraduate numbers are always slower to recover than graduate students; it’s a slower dinosaur,” she said. “We are optimistic that this isn’t just a return to pre-pandemic levels but an indication of sustained growth from a wide variety of countries. But even if the numbers settle, they’ll be settling at a higher level.”

Still, given looming political threats to visa procurement, steadily rising tuition and competition from cheaper destinations like Canada, Brustein isn’t convinced that the sun is rising again on the once-thriving internationalization movement in U.S. higher ed.

“Have the golden days returned? I want it to be a bright new day, but I’m skeptical,” he said. “I still see dark clouds on the horizon.”

_0.png?itok=VPZId1Ui)