You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

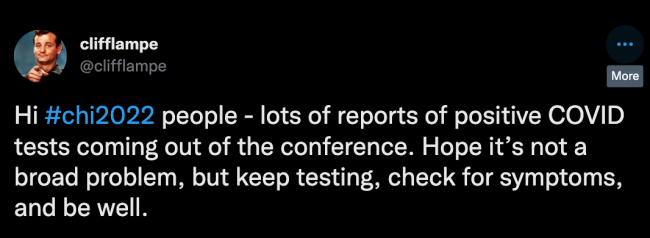

Twitter/Cliff Lampe

Multiple disciplinary organizations have resumed in-person conferences over the last year. And through a combination of careful planning and luck, they’ve largely avoided becoming superspreader events.

Even so, the threat of COVID-19 at mass indoor gatherings remains very real: just ask the 1,900 scholars of human-computer interaction who gathered in New Orleans from April 30 to May 5—or at least those who tested positive for the coronavirus during and after the conference. Some of them are easy to find and have shared their status and experiences on Twitter under the meeting’s hashtag, #CHI2022. Others are privately notifying those they were in close contact with during the event.

So how did the Association for Computing Machinery’s CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems become a hot spot for COVID-19 transmission? Event organizers required proof of vaccination and verified it via a third party; mandated masks except when eating, drinking or presenting; and planned for social distancing during meeting sessions. Attendees also agreed to self-monitor for symptoms and report positive tests to the parent computing association as part of registration. And because about 1,900 additional attendees opted for the hybrid conference’s virtual component, the in-person gathering was about half its typical pre-pandemic size.

Cliff Lampe, professor of information at the University of Michigan and CHI 2022’s general chair, said that the event required all major interventions except for proof of negative COVID-19 tests, due to concerns about logistics and the cost of such tests. So, again, what went wrong? Lampe said he hesitated to play “armchair epidemiologist,” but he noted the “permeability of the conference boundaries.”

“A lot of our members were at [New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival] during the weekend, and you couldn’t walk into a coffee shop or a restaurant without seeing our members,” he said. “And, you know, my mask discipline fell apart a little bit when I went to dinners after the event—stuff like that.”

One conference attendee who agreed to speak anonymously about their experiences said that the conference environment itself presented some opportunity for transmission, as “during the break, we would be socializing in a larger conference room to have coffee and snacks, and sit together to chat, where people were mostly unmasked.”

The attendee said they felt some flu- and cold-like symptoms on May 3, but they didn’t suspect it was COVID-19 until they began to hear talk of other positive cases.

Lampe said he only became aware of positive case reports on the final day of the conference, but as a volunteer organizer, he did not have access to any earlier reports that may have been made directly to the parent computing association, due to concerns about medical privacy.

‘Was It Worth Attending in Person?’

A group of human-computer interaction scholars unsuccessfully petitioned CHI 2022 organizers in the fall for an all-remote conference, to promote equity and access during the ongoing pandemic. Among them was Jennifer Mankoff, Richard E. Ladner Professor in the Paul G. Allen School of Computer Science and Engineering at the University of Washington, who reluctantly decided to attend the hybrid conference in person. In a write-up of her experiences there, Mankoff said, “In the end, was it worth attending in person? I absolutely benefited from the time away and the networking opportunities. Depending on whether I test positive, the scales may tip the other way, though.”

Regardless, she continued, “my belief that CHI should not have been in person stands firm. My opposition to an in-person CHI was never about my personal gain—it was about equity for all of the people who would like to attend and the risk to attendees. Both of those continue to be concerns. Particularly so if we move away from innovations that convey the benefits of in-person conferencing for remote attendees.”

Another in-person attendee who rejected CHI 2022’s virtual option over concerns that it would provide an unequal experience (such as by prioritizing in-person attendees’ questions over remote attendees’), and who has since tested positive for COVID-19, said they wanted conference organizers to know that “we need to prioritize a remote and virtual experience and leave in-person gatherings to regional organizers. It’s safer and fairer for everyone.” (Of course, many scholars say they prefer in-person conferences. CHI 2022 also managed to be almost truly hybrid, clearing technological and financial hurdles that other organizations have said prevented them from presenting fully hybrid events during the pandemic—although Lampe said it’s unclear if this model is sustainable going forward for the same reasons.)

It’s unclear how many attendees tested positive. Lampe said he and other organizers would like to follow up with in-person attendees, but surveying scholars about this issue also poses medical privacy concerns.

As for lessons learned, Lampe said, “I’m glad that we offered a strong online option, because we knew this is a risk. And, you know, for some people that risk was realized. So I would say offering strong online options for the near-term future is very important. And the other thing is we need to have, as a conference group, is a better way of tracking these things.”

“Was it worth it? Would we do it again?” Lampe mused. “I would leave that up to every individual attendee to decide for themselves.”