You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Varying definitions on the qualifications of a first-generation student can change the group’s characteristics, according to a recent analysis of application data.

Drazen_/E+/Getty Images Plus

Understanding the experiences and needs of first-generation college students can be a challenge for college and institutional leaders, in part because there is no common definition of a first-generation college student.

The 1998 Higher Education Act Amendments identifies a first-generation college student as someone for whom both parents (or parent, in the case a student resides with and receives support from only one) did not complete a baccalaureate degree, and this definition has served as the qualification for TRIO participation, as well.

However, that criteria does not take into account the experiences of students whose parents earned college degrees in other countries or students who have older siblings or grandparents who earned college degrees, who may face different barriers to completion and retention compared to their continuing-generation peers.

New research from Common App looks at how ranges of parental degree attainment can have an impact on which students are classified as first-generation and how, even within the first-generation band, student experiences vary.

Methodology

Common App pulled from its applicant data to generate three briefs, using data from 9 million domestic students (U.S. citizens or permanent residents) from 2013 to 2022 who submitted at least one college application.

To identify first-generation students, Common App asks proxy questions, for which students identify the highest level of education their parent(s) have completed.

State of play: Across applicants in the 2022 season:

- 30.4 percent do not live in a household with both parents.

- 11.6 percent have limited information about one or more parents.

- 26.6 percent of students’ highest parental degree level was bachelor’s (the greatest share among applicants).

- 8.8 percent have parents who obtained a bachelor’s, but from outside the U.S.

- 29.7 percent have parents who didn’t obtain a bachelor’s degree but still attended some college.

- 19.2 percent of students reported two parents with no college attendance, the most common parental degree combination.

A quarter reported both of their parents did not attend college, 5.2 percent said one parent had some college but no degree, and 5.5 percent said at least one parent held an associate’s degree, making 37 percent of applicants first-generation (if bachelor’s degree attainment is the threshold).

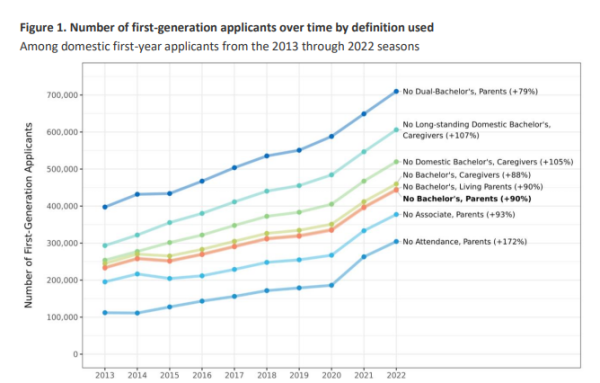

Defining first gen: Common App’s research found the benchmark for what makes a student first-generation can influence both the number of students who fall into that category as well as the demographics of the group.

The broadest label (no dual-bachelor’s by parents) compared to the narrowest (no college attendance by parents) shows variance of almost 400,000 students.

“Thinking about this in more concrete terms, these differences would likely create substantial changes to any programs or initiatives catering towards first-gen students in terms of participation, funding, staffing, and other resourcing considerations,” according to the brief.

These parental education bands also align with variation in the socioeconomic status of first-generation students. For example, if first-generation students are defined by not having two parents with a bachelor’s degree, just under 50 percent of these students are considered low income. If no college attendance by parents is the definition, two-thirds of first-generation students are considered low-income. Similar shifts happen when looking at average numbers of AP tests passed and average number of college applications submitted, students in the various groups perform at higher or lower levels depending on how first-generation is determined.

Continuing-gen students: The research also identified interesting trends among students whose parents had completed a bachelor’s degree or higher. Parental education, overall, provides similar predictive power about college readiness compared to using first-generation status, underrepresented racial minority status, high school type and fee waiver eligibility for submitting the Common App.

Students with higher levels of parental education, measured by either the highest parental degree or combination, are more likely to be considered college ready (scaled GPA) and are more likely to have a higher socioeconomic status.

The one exception is students who report only one parent on their application, because they generally are outliers compared to their peers in the same highest parental degree group, which speaks to the unique challenges of single-parent households. “It may thus be of value for programs and institutions to consider tracking single-parent families separately from first-generation status as another indicator of socioeconomic status,” according to the brief.

So what? Common App’s research identifies two key themes in supporting first-generation student success: the importance of a singular definition of first-generation and use of institutional data, explains Brian Heseung Kim, Common App’s director of Data Science and Analytics.

A clear definition about who is a first-generation student benefits the institution internally and the learner because it helps staff and faculty members figure out who may need additional support in college and what kinds of interventions are necessary.

For example, if a university has a narrow definition (students whose parents or siblings have never attended a postsecondary institution), access to and visibility within the collegiate experience would be the most important interventions, helping guide learners through the hidden curricula of academia. But, if a student is first-generation if neither parent has a bachelor’s degree, helping students retain and persist beyond enrollment may be most helpful in their college experience.

Beyond creating a shared definition, college and university leaders should dig into the data they have on first-generation students and continuing-generation students to curate these interventions and recognize the unique characteristics of their learners, Kim says.

Common App regularly provides member institutions with the demographic data it collects, but fewer colleges and universities create data pipeline processes in which they equip their own systems with this information. Kim sees an opportunity for Common App to evaluate which of its institutions are using data and how data analysis can be further encouraged.

We bet your colleague would like this article, too. Send them this link to subscribe to our weekday newsletter on Student Success.