You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Most colleges are failing to track the performance of their students who are veterans or active-duty members of the military, according to the results of a new survey, and most do not understand what can trip them up on the way to graduation.

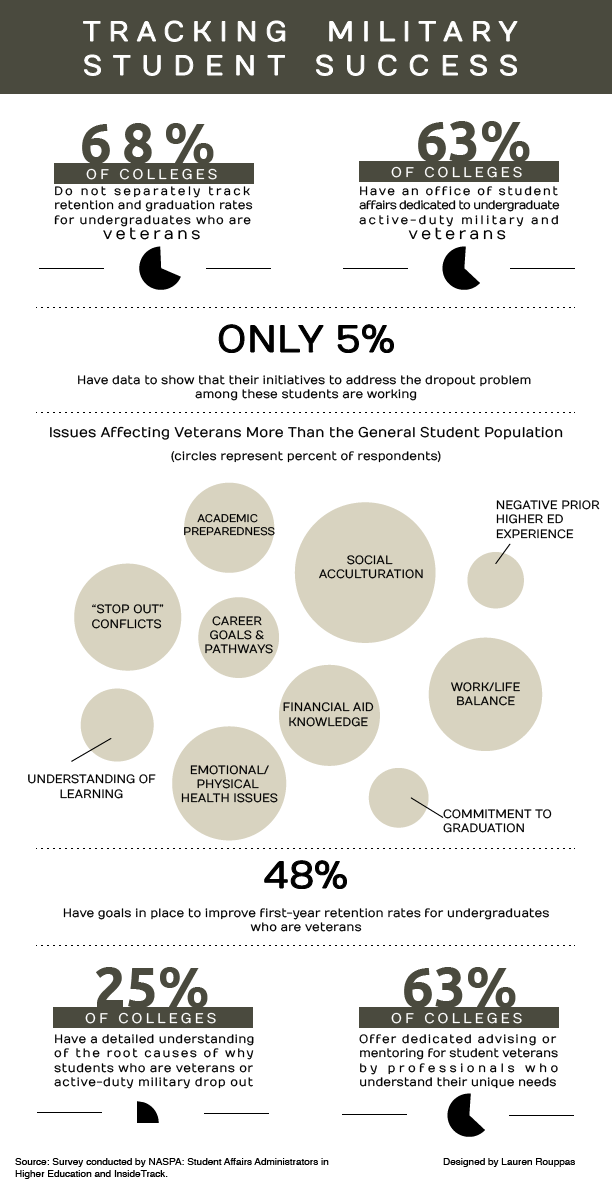

About 68 percent of institutions said they do not separately collect retention and completion rates for undergraduate veterans, according to findings from the survey, which was conducted by NASPA: Student Affairs Administrators in Higher Education and InsideTrack, a company that works with colleges on student coaching services. Only 10 percent of respondents said they know the first-year retention rates of student veterans.

However, the survey found that most colleges have in place specialized student services for veterans, and are generally aware of the need for more information about how the population is faring. (See graphic at the bottom of the article.)

The study is timely, given the large numbers of veterans who served in Iraq or Afghanistan and are enrolling on campuses or online after returning to a down economy. Nearly 2 million veterans are eligible for federal aid aimed at them or their family members.

Wick Sloane on Veterans

Our columnist has led the way on commentary on military service members on campus. Among his essays:

- His annual survey of veteran enrollment at elite colleges.

- A proposal to create free summer school programs for veterans.

- An essay on understanding student veterans in the classroom.

Many veterans face extra challenges after enrolling, such as adjusting to a less structured environment or mental and physical health issues. Yet only one in four colleges reported having a detailed understanding of why veteran and military students drop out, according to the survey.

Results from the survey, which included responses from a broad sample of 275 institutions, are preliminary and not yet ready for public release. But the main findings will not change, said an official with InsideTrack. The two organizations plan to release the full results early next year, after working through a more detailed breakdown of the data.

The survey was conducted to set a baseline for understanding where colleges are in measuring “soldier-to-student success,” according to officials from the two groups. The data build on prior research about student veterans by NASPA, the American Council on Education, and the American Association of State Colleges and Universities.

Dave Jarrat, a spokesman for InsideTrack, said the goal of the new research is to help colleges identify how to best track retention of student veterans, and to promote approaches to student affairs that improve their success rates.

“Now’s the time for setting measurement standards,” Jarrat said. “Let’s note where we are so we can see where we’re going.”

For many institutions, that means starting at square one. Colleges generally follow cohorts of minority, lower-income and first-generation college students as they progress, said Jarrat. But students with military backgrounds don’t get the same specialized attention from institutional researchers.

That should change, he said. Veterans face many of the same obstacles that other adult students wrestle with, chiefly balancing work and family demands while returning to the classroom for the first time in years. But they have several distinctive adjustments to make to the academic environment, according to experts.

For example, the survey found that more than 60 percent of colleges reported that “social acculturation” or “university community issues” have a bigger impact on the retention of student veterans than on the broader student population.

Those challenges might not seem obvious to a non-veteran. For example, Jarrat said that students with military backgrounds sometimes struggle with the relatively flexible schedule of college. “They’re coming from a place of extreme structure,” he said. And that adjustment pang might be particularly acute in online programs, which often have elements of self-pacing and, as a result, are attractive to adult students.

On the positive side, colleges clearly understand that veterans have distinctive needs. Among respondents, 63 percent said they have an office dedicated specifically to student affairs for undergraduate veterans and active-duty members of the military. And 63 percent have dedicated advising, mentoring or coaching options in place for student veterans.

Many colleges have recently begun exploring what works best for student veterans. The survey found that 24 percent had just begun looking into the root causes of why some veterans fail to earn a credential, with another 35 percent reporting that they have some initial ideas that need further exploration.

Jarrat said it is an opportune time for institutions to “make sure that we stay on course and get the structures in place” to encourage student success among veterans.

It’s not surprising that colleges would be somewhat unprepared for the influx of veterans, said Steve L. Gonzalez, assistant director of the American Legion’s national economic division. The increase of student veterans has been the fastest since just after World War II, and he said that colleges took a while to figure out how to best deal with student veterans back then, as well.

Gonzalez agreed with Jarrat that many institutions, both individual colleges and at the public university system level, were aware of the need to better understand veterans and have made progress in the last year or so.

“The schools are playing catch-up,” Gonzalez said. “It’s going to take time.”

Colleges are optimistic that their faculty and staff members and non-veteran students have a positive effect on the retention of undergraduates who are veterans or active-duty military. For example, three-quarters of respondents said faculty members make a positive difference, while only 6 percent reported a negative influence for faculty.

Jarrat said he was surprised by those high marks, particularly given some past tensions between higher education the military, like controversy over Reserve Officers Training Corps groups on campuses.

“It seems that attitudes are starting to shift,” he said.