You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

House Bill 2735 is near passage in the Arizona Legislature. Debate over it has focused on the University of Arizona.

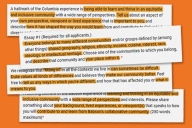

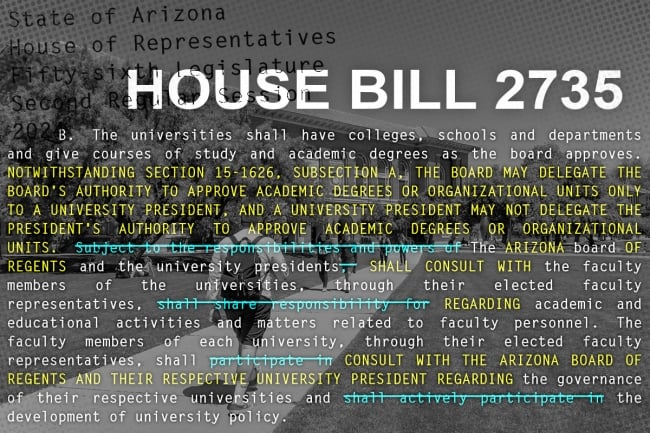

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | Photo: Wolterk/iStock/Getty Images | Documents: Arizona Legislature

Arizona lawmakers are close to passing a Republican bill that would downgrade faculty members’ role in shared governance of public universities while bolstering the clout of presidents and state regents.

Currently under Arizona law, the faculty “shall participate in” or “share responsibility for” governing, academic and personnel decisions. Under the new bill, professors could only “consult with” university leaders on such decisions.

The impetus for this change is a bit of a mystery: House Bill 2735’s prime sponsor, Republican representative Travis Grantham, has said it’s related to financial issues at the University of Arizona, but it’s unclear how. That financial crisis, brought on largely by the flagship university miscalculating its amount of cash on hand by millions, was caused by administrative issues—not by any problems with faculty power. Yet Grantham has stressed the need to reiterate the power of the University of Arizona president, in particular; faculty senate members have argued the bill would increase the president’s power.

Grantham, who didn’t respond to interview requests Friday, has made some critical comments about faculty members. He’s told the Arizona Daily Star that University of Arizona faculty members “took control” of the university and that “the most left of the left” are “grabbing and clinging to power.” He went on to say they should take civics classes because they don’t understand the legislation, and that he doesn’t know or care who caused the financial crisis on the campus.

HB 2735 is just one of multiple bills that GOP-controlled state legislatures have pushed this year that threaten to diminish faculty members’ power and freedoms. Two weeks ago, Indiana’s Republican governor signed legislation that could deny and revoke tenure for faculty members who don’t foster enough “intellectual diversity” to satisfy their campus boards. Last week, Alabama’s governor signed a ban on professors requiring course work that advocates for “divisive concepts”. And earlier this year, Arizona Republicans proposed a “grade-challenge department” that could change professors’ assigned grades for students who accuse them of political bias—though the legislature has yet to pass that bill.

Grantham’s bill doesn’t specifically target diversity, equity and inclusion as do the Indiana and Alabama bills, and it doesn’t directly mention politics, like the grade-challenge bill. Instead, it’s taking aim at a cherished academic tradition.

Legislation diminishing shared governance isn’t without precedent. Senate Bill 266, Florida’s wide-ranging higher education bill last year, drew media attention for banning state dollars from going to diversity, equity and inclusion programs at public institutions. But it also said that public university presidents and the administrators to whom they delegate hiring authority are “not bound by the recommendations or opinions of faculty or other individuals.”

Arizona codified shared governance in state law over 30 years ago, which may have helped protect faculty members’ say within universities from being eroded by administrators or the Arizona Board of Regents, which oversees Arizona State University, the University of Arizona and Northern Arizona University.

Ted Downing, a University of Arizona Faculty Senate member, worked with lawmakers on the 1992 law back when he led the American Association of University Professors’ state arm. “The bill had strong bipartisan support, we only had two opposing votes out of both the House and the Senate,” Downing told a state Senate committee last week.

“The law you’re being asked to gut grew out of a legislative concern over public accountability, transparency and costly administrative bloat,” he told senators. “That’s what was happening in ‘92 and it’s returned.” Downing said the bill established “an early warning system” where a faculty senate could “identify mischief, could identify waste and mismanagement going on within the organization.”

Shared governance’s presence in state statutes may have helped protect it in the past, but that feature has now made it vulnerable to conservative lawmakers.

Leila Hudson, the elected chair of the faculty at the University of Arizona, said she’s worried about the bill transferring more power to the president of her university, Robert C. Robbins, and the Arizona Board of Regents (ABOR), given their track record. She said that “a corollary of the concentration of the sole power over degree programs and units is that the president could eliminate them.” That’s no small worry: The University of Arizona is facing a possible $177-million shortfall, a crisis it apparently discovered in November, and deep cuts are expected.

“The concentration of power in the hands of a single executive with president Robbins’s track record, subject only to the oversight of an unaccountable board with ABOR’s track record, and the elimination of the checks and balances on that power provided by the statutory obligations on elected faculty representatives is terrifying,” Hudson said.

In an email, a Board of Regents spokeswoman said it “signed in as neutral on this bill.” A University of Arizona spokeswoman said “the board has not taken a position on this bill and so President Robbins has not taken a position.”

House Bill 2735 never went through Arizona’s House education committee, which is supposed to specialize in education legislation. House leaders instead sent it through the appropriations and rules committees. On Feb. 28, it squeaked through the House in a 31-to-28 party-line vote. Last Wednesday, the Senate education committee passed it and, if the full Senate passes it, it will head to Democratic governor Katie Hobbs’s desk.

If Hobbs vetoes the legislation, at least two-thirds of lawmakers in each chamber would have to vote to overturn the veto—meaning a number of Democrats would have to vote with Republican proponents. Hobbs’s office didn’t return Inside Higher Ed’s request for comment Friday, and the Arizona Luminaria reported last week that the governor’s office hadn’t responded to multiple requests for comment.

Grantham has argued that his bill doesn’t really do anything. He also connected it to University of Arizona’s financial issues, but University of Arizona Faculty Senate members have countered that the crisis has nothing to do with them.

According to a video of the meeting on the Legislature’s website, Grantham told Senate Education Committee members Wednesday that “I’m almost running a bill to restate current law. The U of A has strayed from what the law intends and how the law is designed to work. ASU didn’t have this problem, NAU doesn’t have this problem, this is a U of A problem.”

Nonetheless, the bill would affect all three of the state universities.

“This is simply clarifying and reinstating … what already exists in state statute, and that is that the president of the university is in charge of the university, that’s why they have a president, that’s why it’s called a president.” Grantham said. He said presidents will continue to take input, “but those faculty and staff don’t make the decisions, the president makes those decisions.”

Mark Stegeman, an associate economics professor at the University of Arizona and parliamentarian for its faculty senate, told the committee the bill “would reduce accountability and oversight.”

“There have been well-publicized administrative issues at U of A recently—none of them have anything to do with the Faculty Senate. The Faculty Senate does not approve the budget, the Faculty Senate does not review the budget, the Faculty Senate does not receive the budget even, normally, does not monitor spending,” Stegeman said. “It is not a roadblock and I don’t know what problem this bill purports to solve.”