You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

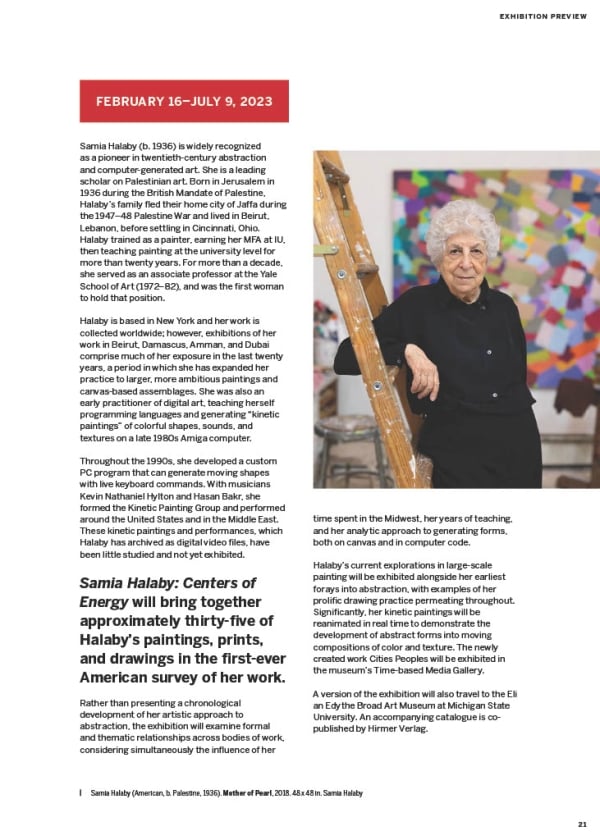

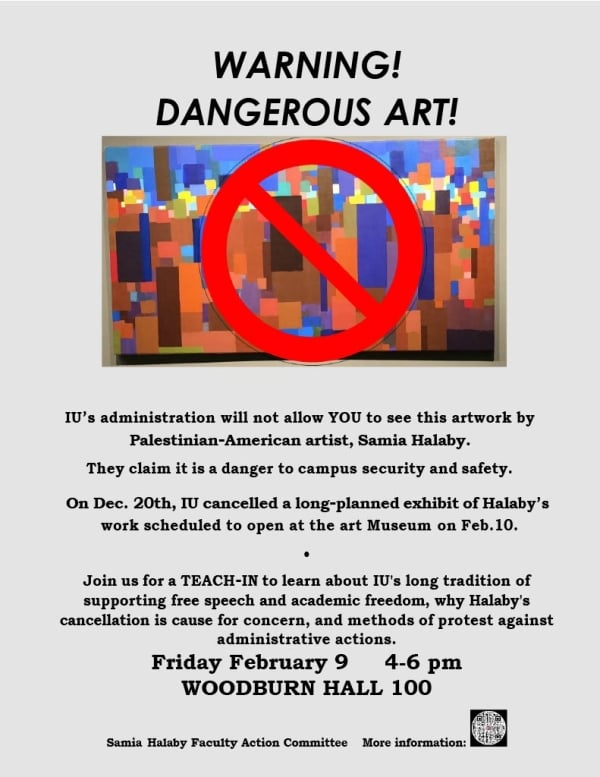

Detail from a flier for a teach-in at Indiana University at Bloomington, protesting the university’s sudden cancellation of a long-planned exhibition by Samia Halaby, an internationally known Palestinian American abstract artist and IU alumna.

Alex Lichtenstein

Nearly six months after the Israel-Hamas war unleashed a steady tide of student-led protests on college campuses across the United States, Indiana’s public flagship university is emerging as a free speech battleground.

The latest dispute is over the abrupt cancellation of a long-planned art exhibition at Indiana University at Bloomington’s Eskenazi Museum of Art, Samia Halaby: Centers of Energy. Halaby is an internationally recognized Palestinian American abstract artist.

The exhibition was set to open earlier this month—IU had already printed promotional materials for it—but university leaders cited vague security concerns when they canceled it in December.

Critics of the decision think there’s more to the story. And while they don’t know the specific factors driving the decision, they can’t ignore the pressure IU administrators have been under since Indiana congressman Jim Banks threatened to withhold federal funding from the university if they don’t adequately address perceived antisemitism on campus.

A preview of Samia Halaby’s upcoming exhibition was featured in the Eskenazi Museum of Art’s Fall 2023 magazine.

Eskenazi Museum of Art

In the wake of Banks’s demands, IU barred a tenured professor from teaching until next fall after he improperly booked an event space on behalf of the student-led Palestine Solidarity Committee. The student group needed the room to host Miko Peled, an Israeli American activist and author who has advocated for the creation of one democratic state with equal rights for Israelis and Palestinians.

Students, faculty and free speech advocates have spoken out against those incidents. But their attention of late has turned to protesting the cancelled exhibit.

Halaby, a 1963 graduate of IU and former faculty member, was forced to flee Palestine with her family during the Arab-Israeli war of 1948 and moved to Ohio as a teenager in the 1950s.

“I always thought of the Midwest as my second home,” she said. “My first thought when they canceled the exhibit was that I lost my second home.”

Her exhibition, which is still scheduled to open at Michigan State University in June, was designed as a retrospective of her decades-long career. Some of the featured artwork dates back to the 1960s, and the exhibit includes a piece from Halaby’s private collection titled “Our Beautiful Land of Palestine Stolen in the Night of History.”

“Our Beautiful Land of Palestine Stolen in the Night of History” by Samia Halaby, 2016.

Samia Halaby

Halaby said university officials never specified the security concerns that prompted them to cancel her exhibit. She believes there was a different reason for the cancellation.

“There’s no way Indiana didn’t know who I was,” said Halaby, who has expressed support for her native Palestine both before and after the Israel-Hamas war started on Oct. 7. “It is my being Palestinian they object to, not to my artwork.”

Since the cancellation, students and faculty who oppose the cancellation have led three separate protests on and off campus this month, including a sold-out alternative event, “Samia Halaby Uncanceled!” at the Buskirk-Chumley Theater in Bloomington, which featured video presentations on her art and life.

Numerous national organizations, including the Middle East Studies Association, the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, and PEN America, have also sent letters to IU president Pamela Whitten asking her to reinstate Halaby’s exhibition. And an online petition started by Halaby’s grandniece with the same message had more than 15,400 signatures as of Sunday.

“They were worried my show would cause upheaval at the university,” Halaby said. “But it was the absence of my show that caused the upheaval.”

‘Potential Lightning Rod’?

Rahul Shrivastav, IU’s provost and executive vice president, addressed the outrage at a Bloomington Faculty Council meeting on Jan. 16, noting that the decision was not influenced by anyone outside of the university.

“We had clearly competing values. We had an exciting debut exhibit of a major international abstract artist and alumna three years in the making,” he said. “We also had a potential lightning rod at a charged political moment that might draw ongoing or major protests and require significant and long-term security we would need for hundreds of other events.”

What’s happening at IU is part of a larger pattern of college administrators cracking down on free speech amid fierce political criticism of institutional responses to antisemitism on campus. And that environment has already fueled the resignations of the presidents of the University of Pennsylvania and Harvard University. Whitten herself came under fire last fall for statements she made regarding the Israel-Hamas war, with some critics pressuring her to support Israel and others demanding she also support Palestinians.

“During these times of serious political intrusion, it’s more important than ever that administrations and boards of trustees stand up for academic freedom and for the crucial role that universities play in society,” said Mark Criley, senior program officer for the American Association of University Professors’ Department of Academic Freedom, Tenure and Governance. “That involves protecting that which is controversial, thought-provoking and may be a lightning rod for protest.”

The IU administration’s explanation hasn’t satisfied students and faculty who say the canceled art show is another example of IU chipping away at freedom of expression on a campus some once thought of as committed to such principles.

Alex Lichtenstein, a professor of history and American studies at IU, organized a teach-in on Feb. 9 that drew more than 100 people to “consider the grave threat such actions pose to the future of academic freedom for everyone at Indiana University,” according to a new release.

Lichtenstein led a teach-in at IU on Feb. 9.

Alex Lichtenstein

“The cancellation of the exhibit for whatever reason is clearly an attack on academic freedom at IU,” he said. “If they’re willing to cancel that, then they’re willing to cancel anything.”

Lichtenstein has taught at IU for more than a decade, and he said he’s generally thought of it as an institution with a strong commitment to academic freedom. But this academic year—which started off with questions about how IU should respond to the Indiana General Assembly’s ban on funding for the Kinsey Institute, the university’s historic sexuality research center—has been different.

“I’ve never seen so many faculty this riled up,” he said. “Obviously, the national climate has dramatically changed. But university leadership has a choice, which is to go with the flow—which is what they’re doing—or to stand up for the university as an ideal.

“There’s a pretty deep sense on the campus that for whatever reason this university administration is not inclined to stand up for this set of ideals,” Lichtenstein said. “Who they’re afraid of, I just don’t know.”

Dozens of faculty and staff at IU’s Eskenazi School of Art, Architecture and Design wrote an open letter dated Feb. 7 decrying the cancellation.

“We believe that the administration’s cancellation of Halaby’s exhibition undermines the university’s stated mission to uphold academic freedom, to protect constitutional rights to free speech, and to affirm our commitment to all members of our community,” the letter said.

Graduate students from the art school also penned a letter to Whitten on Jan. 19, asking, if IU won’t “stand with a multifaceted, celebrated artist and distinguished alumna, what sort of loyalty can the rest of us hope for?”

As a result of the cancellation, the school of art has “already experienced collateral damage,” the faculty letter said.

Nina Sarnelle and Selwa Sweidan, two artists who had already made arrangements for a trip to Bloomington this month as part of the McKinney Visiting Artists Series, wrote to IU’s president and provost on Feb. 1 to say they were considering backing out (they have since officially canceled their appearance) as a show of solidarity with both Halaby and Abdulkader Sinno, the sanctioned IU professor.

“We find institutions canceling engagements with Palestinians, shutting down solidarity groups, and abusing the term ‘antisemitism’ to justify sweeping censorship,” Sarnelle and Sweidan wrote. “This kind of activity, including the unfair treatment of Halaby and Sinno by Indiana University, contributes to the dehumanization of Palestinians and undermines the potential for peace and justice in the Middle East.”

Another artist, the faculty letter said, vowed never to return to IU after it canceled Halaby’s show.

“We can only anticipate further challenges recruiting faculty, students and visitors disinclined to participate in an academic environment with such tight administrative control over creative activity and research.” Although the authors of the letter said they “remain unconvinced of the rationale behind the show’s cancellation,” they suggested that “if there are indeed legitimate threats,” the university could shorten or postpone the exhibit to ensure safety measures.

In an email Wednesday, IU spokesman Mark Bode did not respond to questions about the university’s intent to reschedule the exhibition and instead reiterated that “Academic leaders and campus officials canceled the exhibit due to concerns about guaranteeing the security of the exhibit for its duration.”

And without further explanation from IU’s administration, faculty and students are leaning on the broader context of campus, state and federal politics to fill in the blanks about why Halaby’s show was scrapped.

‘Security as a Smokescreen’?

“I think they are using security as a smokescreen for other efforts. It is so opaque to me,” said Heather Akou, an associate professor of fashion design who signed the faculty letter. “All I can see is the pattern of things that have occurred and who has been impacted.”

At the same time that IU is clamping down on pro-Palestinian speech and expression, the Indiana General Assembly is considering a bill that would give the university’s governing board the authority to judge the “intellectual diversity” of faculty in hiring, promotion and tenure as well as, if it passes, newly mandated post-tenure reviews.

Both Whitten and local chapters of the AAUP have criticized the bill, with one member of the AAUP characterizing it as “a blank check to fire people based on identity or politics or for complaining about corruption, for complaining about discrimination.”

Akou said the bill, coupled with Halaby’s canceled exhibit and the sanctioning of Sinno, the professor who sponsored the Palestine Solidarity Committee, is changing her perspective on IU and Indiana.

“Over the last few years, IU was making progress toward making a greater diversity of people feel welcome on campus. I hate how all of these events have set us backward,” she said, adding that for the past few years she’s been watching Florida and Texas strip tenure protections and funding for diversity, equity and inclusion programs.

“I was so grateful things moved slower in Indiana and it hadn’t hit home. Unfortunately now it’s hitting home.”

‘Critical Juncture’ for Higher Ed

Tom Ginsburg, a law professor at the University of Chicago and faculty director of the university’s Forum for Free Inquiry and Expression, spoke at the teach-in at IU earlier this month.

“They had to vet my appearance,” he said. “In some ways that’s very dangerous to the idea of a university, because it suggests we aren’t a decentralized community of learners and scholars but in fact a decentralized operation in which the university is responsible for every speaker that comes.”

He said canceling Halaby’s exhibition amounted to censorship and pointing to unspecified security concerns to justify the decision played on tropes about the inherent danger of Muslim people. But such moves are not unprecedented.

“This is an idea that first emerged on the left,” Ginsburg said, noting that for years students have argued that certain conservative and far-right speakers have made them feel unsafe and therefore shouldn’t be allowed on campus. “It’s natural that that kind of language would be repurposed.”

The intensity of this particular political moment, however, has put higher education institutions at a “critical juncture,” he said. “We need to remind ourselves that the purpose for a university is inquiry and not politics or political mobilization.”